U.S. Army Vietnam War West Chicago, IL Flight date: September, 2019

By Jack Walsh, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Bill Ziegler remembers when he realized that Vietnam would be an “alternate reality.” His plane had just landed at Bien Hoa when the pilot announced, “We’re getting fire, so get off quick.” When the plane finally stopped, they ran down the stairs, under the plane, and dove into a ditch. “We had fire coming at us, and I’m thinking, ‘Damn, we just got here and already they’re shooting at us! Welcome to Vietnam!’ And that was the start of the alternate reality.”

Bill grew up in Worth, the oldest of eight kids. His dad was a union carpenter and his mom a housewife. After attending St. Laurence High School in Burbank for two years, he graduated from Eisenhower High School in Blue Island. He studied at the Illinois Institute of Technology for a couple of years, majoring in Electrical Engineering and then Business. Then he became a radio DJ in South Bend, Indiana, for WJVA-AM/FM. He liked it, but as is typical in that industry, he lost that job. In July 1968 at age 20, he decided with his college roommate and Theta Xi buddy to join the Army “looking for a little adventure.” They signed up for a two-year regular Army program. Bill’s family had a tradition of serving in the military.

Basic Training was at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, “which was a hell-hole in July and August,” then moved on to Advanced Artillery Leadership and Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. During AIT he was an acting First Sergeant, and after graduation, he received his Sergeant (E5) stripes. His whole group had become artillery section leaders. After training and before he shipped out, he got married.

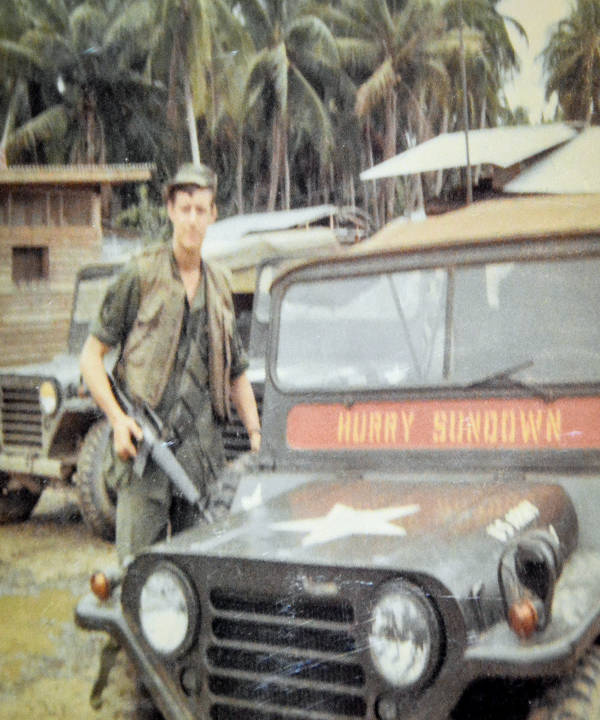

In May of 1969, Bill went to Vietnam, with the 9th Infantry in Dong Tam, with a rare MOS, 17E40, Artillery Chief of Section. He was assigned to a Jeep-mounted searchlight vehicle with a Spec/4, a funny, upbeat, and stalwart African-American named James Dunn from Rhode Island, working under him. The light was the size of a very large, old-style TV, and produced both infrared light, which they monitored with night-vision binoculars, and also extremely high powered visible light. They only worked at night, and their unit’s nickname was “Hurry Sundown,” taken from the name of a Jane Fonda movie. Bill explains “ironic maybe, but from Barbarella and other roles, she was on posters nailed above a million bunks over there, including mine.” They used the searchlight on a variety of assignments.

In Dong Tam they worked the berms, watching for the enemy encroaching. At midnight they used to drive to the small Navy compound on the outskirts of the post for the best meals they ever had in Nam. They enjoyed huge steak and scrambled egg sandwiches on inch thick slabs of toast wrapped in wax paper to go. They worked on area bridges with a squad of Marines watching downstream for Charlie trying to cross during the night. They most often worked on night AP’s (ambush patrols). Bill served the first 6 months with the 9th Infantry and after the 9th returned to the states, did a brief stint working with MACV, then more night AP’s with ARVN’s. These ground forces of the South Vietnamese military didn’t speak English, which made for some interesting situations, to say the least. “One night working in infrared light a G.I. infantry leader said to switch to the very bright visible light when we caught some fire from a nearby tree line. We could see their muzzle flashes already, and the light would have been a huge target for the Viet Cong, with all of us clustered near it. I did not make that switch, and since have wondered if I was being a coward, or just being smart and protective of us all. Probably a bit of each.

“While living in a run-down former open-air hotel in My Tho, Spec/4 Dunn and myself would drive out in the boonies just before dark down the elevated roads between rice paddies well past an intersection. We’d park on the side and point the light on infrared back toward the intersection to watch for Charlie crossing. If we saw anything we would radio in for support. We’d take turns watching and grabbing some Z’s; and one night while sleeping on the road a large lungfish crawled out of the paddy and squirmed under the flak jacket I was using as a pillow. It scared the living crap out of me! I remember another night vividly. We were always tired, as it was hard to sleep during the day with the heat and bright sun and humidity. On this night we both fell asleep. The next morning we started back and found the road blocked with a huge pile of mud Charlie had built to block our exit during the night. On top of the pile they had taken the time to sculpt from mud a small “work of art” picturing a VC, well, let’s just say “violating” a G.I. It took a good half hour to clear the road so we could get back. I’ve often wished I’d saved that little sculpture. I never thought of Charlie as the faceless enemy to be destroyed after that morning. If we’d been awake, we’d have spotted them and they may well have been killed. If they’d been a bit braver, they might have snuck up and killed us. James and I both realized later that the mud pile could have been booby-trapped as well. It gave me a new respect for the enemy as fellow human beings that stayed with me for the duration, and beyond. We were both doing what we thought was right and important for our countries. War is hell indeed.”

For a while, Bill’s unit worked with the “Brown Water Navy,” supporting the Navy patrol boats on the river. Bill was scheduled to go on the river too, but he received a Red Cross message that his wife – who was 8-1/2 months pregnant – had fallen and broken her arm. The baby was born almost 5 weeks later and although he was granted leave to go home (when she really needed his help), he was held at headquarters in Can Tho for 10 days. In the meantime, his unit was being hit hard – “Charlie would go up on the berm and shoot a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) and blow you right off the boat. We lost 5 guys in 3 weeks. But I was stuck at headquarters. By the time I got back a month later, we were back on ground patrol. I believe my wife saved my life by falling down the stairs.

“The thing was I was 20-years-old when I went in, a typical American boy, believing if we’re in a fight, we have to be right. Like others my age, I acted like I was immortal. Once you got to Nam, you just wanted to stay alive and to keep your buddies alive.”

But he does have memories of adventures. “I remember going to Tokyo on R&R, and taking a tour in the mountainous areas around Mt. Fuji, and seeing all the beautiful shrines and the evergreens and the snow – it was absolutely gorgeous. I took the subway system, and I’m on this train, and I’m a foot taller than everybody around me. I had wanted to go to Australia, but that was so popular you had to agree to stay another six months, and I thought, ‘No I’m not going to get shot at for another six months, the Ginza’s good enough!’

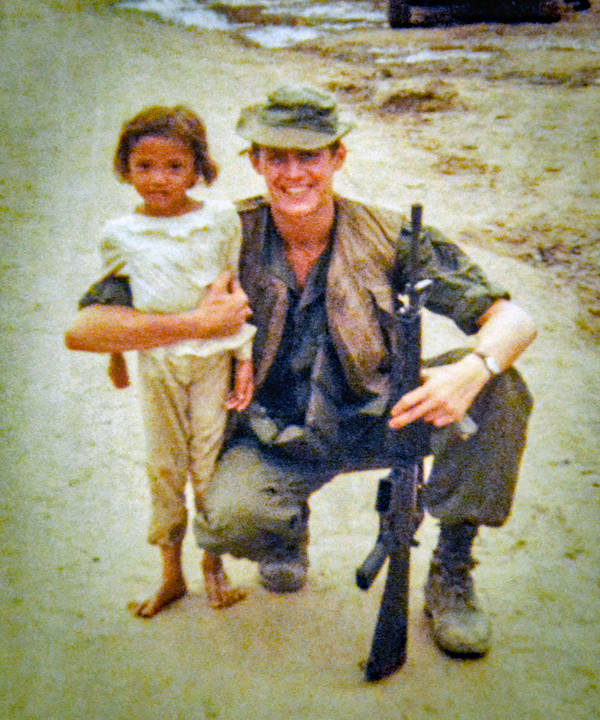

“I bought some wonderful stereo equipment in Okinawa, and had it sent back to Nam, and about 20 percent of it was stolen off the back of the trailer by the little Vietnamese kids when I got back.” Bill also took many photos while in Vietnam with an expensive SLR camera he won in poker game early on.

He remembers that the company HQ had a pet boa constrictor that they fed chicken and rodents. He remembers working bridge control with the infantry, waiting for darkness, shooting grenades downriver trying to blow down palm trees.

“I was in the best shape of my life. We worked the searchlight only at night, so during the day we’d play basketball. I water skied on the Mekong River in full gear, with a metal helmet and flak jacket.”

Bill realizes “I was very lucky. I don’t have any really bad memories from there. I came home without any physical scars, and never had to face any bad reception from people back in the states. I did lose some buddies there, and was shot at and scared for my life. A chopper I was on lost power and went down in the jungle, but managed to land safely and we were rescued without attracting fire. So I was very lucky indeed. We had an expression over there for close calls: ‘Shot at and missed, s**t at and hit.’ It was really a huge adventure, with elements of everything from Platoon to Apocalypse Now.”

By the time he got home 12 months later, he had a family to support, so he got a job working for New York Life Insurance. He worked in sales for a few years, but took a chance to go back to school to become a computer programmer. He excelled at that, and eventually retired from Navistar as a manager. Bill is a member of MENSA, as well as a science and nature buff who can never learn enough about either subject. He’s also an avid motorcyclist and is still riding the same bike his late wife gave him as a 10th anniversary present back in 1991 – the best present ever!

Bill has three children: William Jr., Kimberly and Corina. Ironically, Bill Jr.’s wife Hailey was born in Vietnam, and they’ve visited her family’s relatives there several times. Corina, has a strong sense of wanderlust and has traveled all over the world as a documentarian and teacher. She now lives with her husband and 3 of Bill’s 7 grandchildren, in Hanoi, Vietnam, temporarily – for the adventure, and to save money while her husband completes his graduate degree online.

Bill lives in West Chicago, and is doing his best to enjoy his retirement.