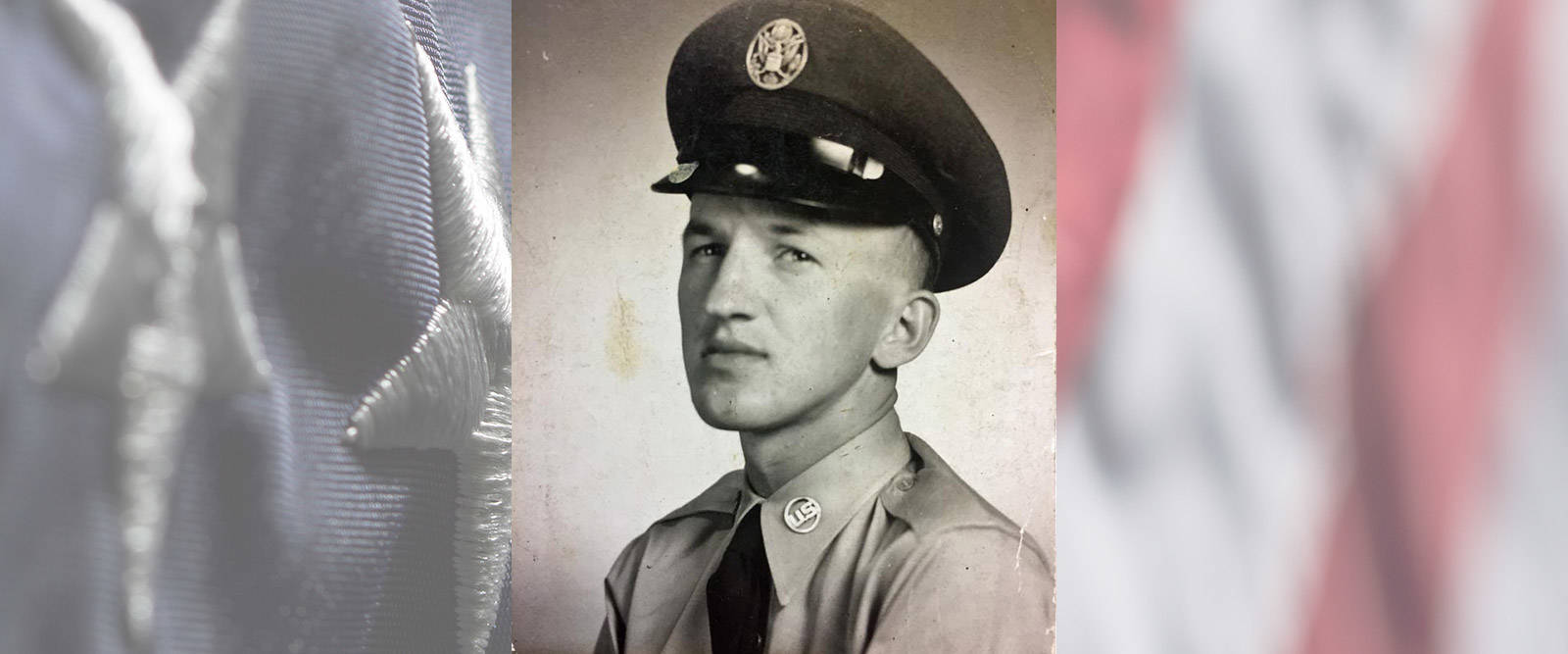

U.S. Army Korean War Orland Park, IL Flight date: 06/06/18

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Wally Ciszak was born in Chicago in 1932 and was raised within walking distance of the old Comiskey Park. He remembers going there and paying a nickel to see the White Sox play. He has been a lifelong fan of the team ever since. Upon graduating from St. Rita High School in 1950, he worked loading airplanes for American Airlines at Midway Airport. His plans for his future, though, were interrupted by the Korean War.

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, Wally was the prime age for soldiers in the conflict, so he knew he’d eventually be drafted. He “didn’t want to get shot at” so he volunteered for the Air Force in 1952. Wally attended 12 weeks of Boot Camp at Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio, TX and upon completion, was sent to weather school. Up until then, he didn’t even know there was a weather service in the Air Force and he’s not sure how he was picked for it, but off he went. Weather school was at Chanute Air Force Base in Rantoul, IL and lasted for three months. In the classes, he learned how to read clouds, take measurements, and read a barometer. Upon graduating, he wasn’t sure where he’d be sent, but the most likely place was Korea, where forty men out of his class of sixty were sent. Wally’s lieutenant asked him if he’d be interested in “Isolation Duty.” This meant being sent to report on weather conditions in remote corners of the globe. The more remote, the shorter the assignment. Some men were sent to “ice islands,” which as the name implies, were large floating chunks of ice on which the Air Force would place men and weather equipment.

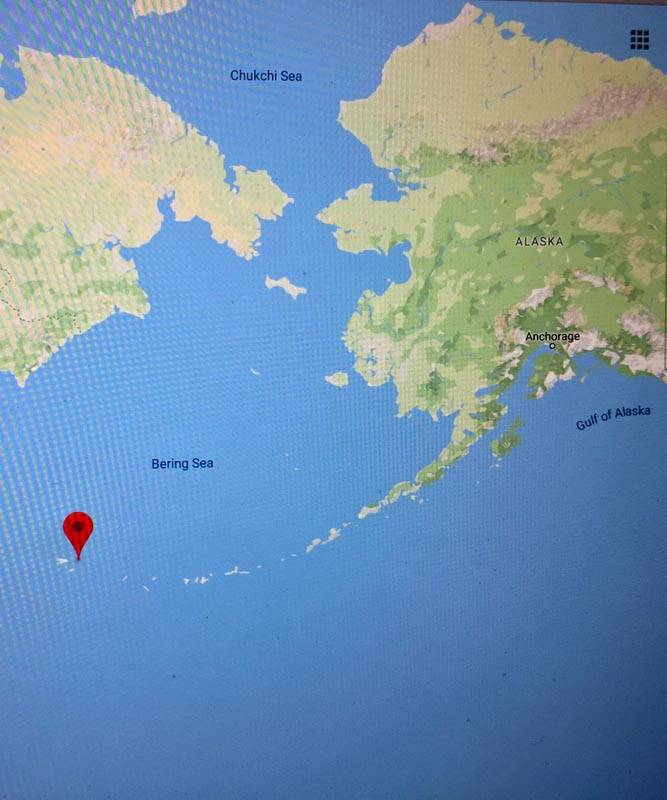

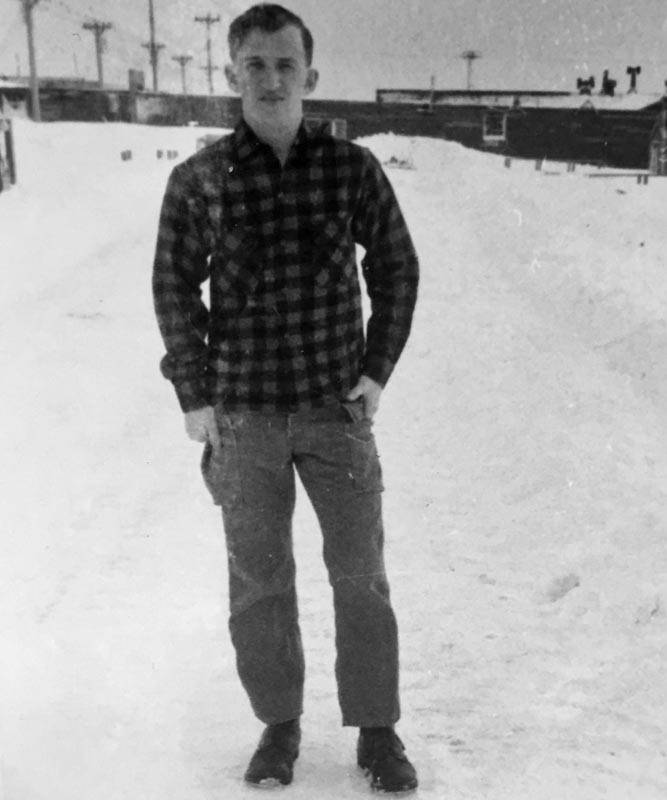

Wally was assigned to Shemya, Alaska, a remote island at the very end of the Aleutian Islands chain. It is 1,200 miles from Anchorage and is significantly closer to Russia than it is to mainland Alaska. In fact, it was only 240 miles from the largest Russian submarine base at the time. Originally established during World War II, it is a three mile by four mile piece of land on which the Air Force had set up a weather station, landing strip and refueling station. Because the currents surrounding the island contained warm water, the temperature was fairly moderate by Alaska standards; but it was almost always foggy.

The Shemya base had 240 men, of whom 30 were weathermen. In this era before satellites, weather information was gathered from bases on the ground. In the case of Shemya, the weathermen would send up a weather balloon every four hours. It went as high as 60,000 feet; a device attached to the balloon would measure temperature, wind speed and other variables. The personnel at the base would compile all the information and then send it via teletype to Anchorage. At the time, both commercial and military flights weren’t able to cross the Pacific Ocean without refueling. Shemya was a refueling stop for transpacific flights, refueling about ten planes per week. Most of the replacement officers going to Korea were sent through Shemya on their way to the war zone.

People assigned to isolation duty had to pass a psychological examination to make sure they were suitable for such duty. Boredom was one of the main problems, as they would be on duty for six days and then off duty for four. Men filled this downtime with card playing and drinking. One time, he gambled his monthly paycheck away in one day. Every month they’d receive a planeload of “the best booze” and occasionally movies which they’d watch over and over. They had nice athletic equipment, but nobody wanted to use it. Wally says, “personally I didn’t find it that challenging to be so isolated, but many people did and each man had to figure out on his own how to deal with it. Men who couldn’t handle the isolation sometimes would get goofy.” Wally recalls initially flying to Shemya, and meeting a sergeant who was going there for his second tour. The sergeant warned Wally that it was terrible and he was clearly unhappy about having to go back. In the year that he was stationed in Shemya, Wally never left except for one week of leave in Tokyo. Wally managed to survive his isolation duty, but after a year, he was definitely ready to leave.

In November of 1953, Wally was assigned to Lawson Air Force Base located within the Army base at Fort Benning, Georgia. The 101st Airborne was based at Fort Benning and the Air Force personnel there helped in the training of the paratroopers. The Air Force personnel would fly the planes and the Army men who “were crazy enough to jump out of them” as Wally says, would parachute down. Whenever there was a jump scheduled, Wally and the other weathermen went to the jump field, sent up a weather balloon and measured the wind so that the pilots and the parachutists would know when to jump. Wally spent fourteen months at Fort Benning.

In November of 1954, Wally left the military when he received a hardship discharge because his father had a stroke and his mother was seriously injured in a fall. At first, he went back to loading planes at Midway Airport, but eventually he went to school to be an airplane mechanic. He realized that he didn’t like getting his hands dirty, so he attended St. Louis University courtesy of the GI Bill and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical administration in 1959. He returned to Chicago and went to work in the international freight business, but after working at several companies in this field, he started his own firm. He gave up the business in 1994.

Wally and his wife Loretta have known each other since first grade. During his time in the military, Wally was engaged to her. They married in 1955, having been married for over 63 years. They have two children and four grandchildren, all of whom live in the area. For a long time, Wally kept in touch with many of his Air Force buddies, but most of them now have passed away.

Despite the hardships in Alaska, Wally feels fortunate that he wasn’t sent to Korea. “What I had to endure wasn’t as bad as what some of the weathermen faced in Korea.” He also feels fortunate to have been part of the Air Force. When he graduated from high school, nearly everybody in his class got involved in the Korean War and they all managed to make it home, but their lives had been forever changed. Wally lived through an earthquake in Alaska and a tornado in Fort Benning. Given the fact that his dad died at the age of 48, he feels fortunate to still be around and able to go to Washington D.C with Honor Flight Chicago. For a long time, he wasn’t sure he deserved to be on an Honor Flight, but he enjoyed his time in the military and says he’d do it again.

We are proud to honor you and your service in the Air Force. Enjoy your well-deserved Honor Flight!