Army Vietnam War Hilton Head, SC Flight date: 08/28/24

By Al Konieczka, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Dr. Stuart Poticha grew up on the north side of Chicago near Wrigley Field. His father was a flight surgeon in the Marine Corps during World War II. After high school Stuart went to John Hopkins University and then came back to Northwestern University where he received his surgical training and completed a five year residency in surgery that ended on July 1, 1965. He was then appointed to the faculty at Northwestern. At the time, he was the youngest surgeon on the staff.

One day, in November of 1965 he was making his rounds at the hospital when a call came over the speaker. Stuart remembered, “I had a bunch of residents and students following me as we were seeing patients. I told them to wait and I’d be right back. I went to the nurse’s station and picked up the phone and some guy says, ‘I’m colonel so and so and I just wanted to tell you you’re going directly to Vietnam.’ I said wait a minute, you must have the wrong guy, I’m not in the Army. That’s how I found out I was in the Army.”

Indeed, the next day Stuart received his draft notice. Stuart completed his basic training at Fort Sam Houston along with about 200 other doctors, 10-15 of which would be going to the 12th Evacuation Hospital. During basic training they mostly learned how to be officers. According to Stuart, “The only actual soldier training during basic was one morning on the shooting range learning how to shoot a .45 and another morning on the range learning how to shoot a rifle. Every person had to qualify with a .45 before going to Vietnam but in the case of the doctors, it didn’t even matter if we hit the target or not, as long as we could fire the weapon.”

After basic training, they sent all of the doctors and hospital support staff – mechanics, drivers, med techs, etc. to Fort Ord in California. They were told they would be travelling any day to Vietnam but as Stuart recalled, “Well, any day turned into two months. And for two months, they didn’t know what the Hell to do with us, especially the surgeons. The hospital at Fort Ord was already fully staffed and they didn’t need us. So we would meet every day at 7am for our orders and we had none so I would play golf or tennis and it was enjoyable for two months.”

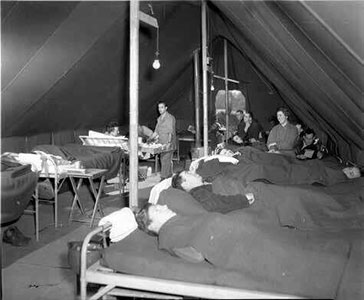

The one thing that Stuart and the other surgeons did during their time at Fort Ord was travel out to the desert by truck and watch the support personnel set up a 400 person hospital out in the middle of the nowhere in just one day. According to Stuart, “The Army was still going by the distribution of hospitals and medical facilities that they used during World War II which was not really applicable to Vietnam. What they were teaching us was that so many yards behind the front lines was the battalion aid station, so many yards behind that was a MASH Hospital, then so many yards behind that is an evacuation hospital. They also told us that our evacuation hospital would be a mobile tent and have to move along with the front lines. That model didn’t work at all for Vietnam.”

Finally, by July of 1966, their group was sent to Oakland, CA and were told they could either fly to Vietnam or go by ship. Stuart chose to go by ship. “They loaded us all onto the ship, the USS Patrick, which was a troop transport ship from World War II. There were about 2,000 people on our ship along with all the medical equipment and they had a complete operating room (OR) on board. The trip took 17 days from California to Vietnam and in the middle of the Pacific I used that OR to perform an emergency appendectomy on a corpsman. By the time we got to Vietnam in September of 1966, everything we had been taught was out the window. There were no front lines. The Army would simply build a base in an area they wanted to protect, and stick a hospital inside there.”

Stuart and the rest of the surgeons, doctors and support staff were sent to a base camp at Cu Chi which was positioned about 25 miles between Saigon and Cambodia. Stuart described the scene when he arrived in Cu Chi. “There was absolutely nothing there. All this business about building a hospital using tents went out the window because of the high temperatures and the rain. The Army had to clear a huge area of land and they built the 12th Evac Hospital consisting of about 25 Quonset huts strung together and set on concrete pads. So while they built the hospital we got shipped off to work at other hospitals. I ended up in the Central Highlands in Pleiku and An Khe working for a few weeks.”

The 12th Evac Hospital was finally built and ready for patients at the end of October, all of the doctors and surgeons were called back. That was when the nurses first arrived and they saw their first patients in early December 1966. Stuart was assigned the role of Chief of Surgery because at the time, he was the only board-certified surgeon on site. A board-certified surgeon is a surgeon who has completed a residency training program and passed a two-part specialty examination.

Stuart recalled that at first the injuries just trickled in and they were minor. “We saw scratches, cuts and other minor injuries. Then they sent out one of the search and destroy missions and all Hell broke loose. We would get helicopters landing constantly with 4 or 5 casualties on a helicopter and 2-3 helicopters landing at a time. Before you knew it, we had 50 patients in the hospital with the most horrible injuries you could possibly imagine. They had arms and legs blown off, holes in the chest, heart injuries, abdominal injuries and tons of soft tissue injuries from shrapnel. We had to operate until we had taken care of all of them. We would sometimes do 36 hours straight with no rest. We would then stumble back to our beds and sleep. The next morning, the hospital was completely empty because as soon as we had stabilized the patients, they were shipped out to another hospital further back.”

The hospital team faced days with unbelievable amounts of casualties followed by days of nothing to do. Stuart explained that they were able to save an amazing amount of lives because of two things. “One was the helicopters that got the wounded out of the hot zones and back to us at the base very quickly. The other thing was an unbelievable supply of blood. An average sized guy will have about 10 units of blood in his body. We had patients who used sometimes 30-40 units of blood during surgery. The reason we had so much blood on hand was that we had 25,000 troops on that base and when we had mass casualties we had a line of soldiers about 3-4 city blocks long waiting to donate blood. There were times the blood was still warm when we were transfusing the patient because it had just been donated.”

Stuart quickly honed not only his skills as a surgeon, but also his ability to detect the type of injury a patient arrived with based on their demeanor. “Most of the guys who were wounded badly were very quiet. They weren’t screaming in pain they would just lie there scared to death or praying. When a guy had a wound to his heart, he would be screaming help me I’m dying. The pressure from the blood loss puts pressure on the sack around the heart and you need to use a long needle to drain that blood and relieve that pressure before you can operate.”

The hospital itself was positioned in the center of the camp, completely surrounded by all the vital parts of the 25th Infantry Division. The camp was on several acres of cleared land with rows and rows of barbed wire and only one entrance into and out of the camp. Each night they would close the gate and park a tank there. Almost every night the Viet Cong (VC) would shoot rockets and mortars into the base. The 12th Evac Hospital opened in December 1966 and closed in 1970. During that period of time, they treated 37,000 injuries – more casualties and the lowest mortality rate of any hospital in Vietnam.

Stuart’s tent was located across the dirt road from the pre-op area and the helipads. “As the Chief of Surgery, I had the front bunk so I could look out and see when the helicopters were coming. In addition to my surgeries, one job was to walk around and look at the casualties and decide which patients to take to which surgeon. Doing triage was the worst. Let me tell you, that was the hardest job I had to do in Vietnam. You would start at one end and a guy follows you with a pad of paper and you have about ten seconds to assess the patient and say one of three things, take him to surgery now, he’s not serious take him to the ER or he’s too badly wounded and not going to make it. And it never ended because by the time you got to the end of the line, ten or twelve new casualties had arrived.”

According to Stuart, most of the visiting dignitaries to the hospital were flown in by chopper, spent a few hours walking around the facility and then left before dark so they could put Vietnam battle ribbons on their chest. The only visitor who was ever interested in what was really going on at the 12th Evac Hospital was a Colonel Thomas Whelan. “Colonel Whelan was the Chief of Surgery at Tripler Army Hospital in Hawaii and Chief of Surgery for the Pacific Theater. He and I would sit down and talk about the most challenging surgeries we faced, what treatments were we using and what techniques we had developed that could help other doctors. He visited 3 or 4 times during my time in Vietnam and we would sit for hours discussing these things.”

On one of the trips to Vietnam, Colonel Whelan invited Stuart to come to Tripler Army Hospital in Hawaii when he finished his tour in Vietnam to help set up a research laboratory. So when Stuart finally left Vietnam in September 1967, he went to Hawaii and served out the remaining 5 months in the Army working at Tripler Army Hospital teaching residents and working on the research lab. Colonel Whelan even wrote an Army textbook used to teach other surgeons about war injuries. That textbook contains many photos provided by Stuart.

Stuart’s job at Northwestern Hospital was held while he was in the Army and he went back to Chicago and started his own practice where he practiced for 35 years. Stuart got engaged over the phone while still in Vietnam to a girl named Cynthia he had been dating before being drafted. She joined him in Hawaii when he returned from Vietnam. They were married for several years and have three children and six grandchildren and a seventh grandchild on the way.

Dr. Stuart Poticha is now approaching 90 years old and walks with a walker and tries to swim daily. Stuart has also written a book about his experiences as a surgeon in Vietnam. It’s being reviewed and will most likely be released in the next six months or so. While attending a medical conference after the war, Stuart ran into a younger doctor he had trained who asked him how to become a really great surgeon. Stuart’s answer was “Go find yourself a good war. You’ll see and experience things in that time period that you could never have imagined. Performing surgery during a war produces the kind of confidence that a good surgeon really needs to be a great surgeon.”

Out of all the life-saving surgeries that Stuart performed in Vietnam, there were only two patients that he couldn’t save.

Dr. Stuart Poticha, thank you very much for your dedicated service and the many lives you saved. Enjoy your well-deserved trip to Washington D.C.!