Navy Flight date: 04/09/25

By Joe Kolina, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

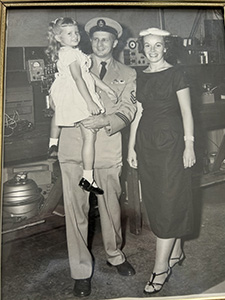

Shelley Morrison can’t remember a time growing up when she didn’t want to serve in the U. S. Navy.

One of her earliest pictures shows a chubby-cheeked infant in overalls sitting on a sofa clutching her father’s white Navy hat with both hands as it sits precariously on her little head. Her father was a Navy lifer. It was the life she wanted for herself.

“It was always there,” she says. “I loved the uniforms, the sailing, everything, the whole Navy life. I just wanted to do it.”

Shelley’s Navy dream came true, but not in ways she ever imagined. She has a gutsy, independent streak that turned her into a Navy trailblazer. It’s a story of tenacity, occasional disappointment, and unexpected adventures and achievements.

It didn’t start auspiciously. Her father was dead-set against it. He was a retired chief petty officer and he knew the prevailing view among sailors. Women did not belong in the Navy.

“He was afraid of what I would run into because of that attitude,” Shelley remembers. It was 1973. “They could make your life miserable because they didn’t want you there.”

But that didn’t stop her. Nothing could stop her.

“It was a roadblock,” she tells me with a laugh. “But I was going to get my own way. Joe, I was just bad.”

Shelley travelled to California from upstate New York on her own to enlist. She was just 19 so she still needed her parents’ permission. She wore them down.

“I forced the issue, “she says. “I think they thought, ‘This is what she wants. She does not want to finish college.’ So they finally signed.”

That wasn’t the only hurdle. Shelley completed recruit training in Orlando, Florida, with the intention of becoming a medical corpsman. She started work as a striker—a kind of apprentice—in a dispensary at Treasure Island in San Francisco. But she felt stuck because there were no places in corpsman school.

“It turned out for the best,” she says. “I didn’t realize what I was capable of doing.”

She soon found out. Orders suddenly came down for 12 WAVES who were unassigned. Six were sent to Pearl Harbor. Six to Adak Island, a remote base in the Aleutian Islands. Shelley was slated for Pearl Harbor. But there was a complication.

“I had a friend who was crying her eyes out,” Shelley recalls. Her friend’s husband was on a submarine stationed at Pearl Harbor. Her friend got orders for Adak Island.

“So we swapped orders,” Shelley says. “The Navy didn’t care. They just wanted a body to show up. So they said ‘sure, go ahead.’”

That’s how Shelley became one of the first group of WAVES to serve on Adak Island. The Navy wanted to see how women fared in isolated outposts. Candidates had to pass a few physical and psychological tests. But preparation was minimal. They were issued short-waisted arctic jackets and told to bring a lot of warm clothes.

Words like remote and isolated don’t do it justice. Adak Island is part of the Adreanof Islands near the western end of the Aleutian Islands in the Bering Sea. It’s the southernmost point of Alaska, nearly 17-hundred miles from the capitol of Juneau. The Navy maintained a station there during the Cold War to monitor submarine traffic.

Weather could get brutal. Sub-zero cold, heavy snow, dense cloud cover and fog. Winds so fierce Shelley calls Adak Island the “birthplace of the wind.” It was deadly dangerous sometimes. The Christmas before Shelley arrived a pilot leaving Adak misjudged conditions and slammed his plane into a mountain on nearby Great Sitken Island. The weather was so bad rescue crews were helpless.

“Because of the snow and ice they could not get anyone in there,” she remembers. “The plane had to sit there until spring when they could go out and get the bodies.”

Nature could also inspire with its awesome power and beauty. Shelley has photographs of a landscape not many people have ever seen. Billowing grey and white clouds cover the skies like tarpaulins. Scavenger birds lurk motionless on telephone poles, ready to pounce. Hulking snow-covered mountains rise in the distance from the bleak frozen tundra that stretches over ancient rock formations. Frigid water surrounds everything.

“Every morning from my barracks window I could see an active volcano on Great Sitken Island oozing lava,” Shelley says with a shake of her head and a look of amazement.

Duty on Adak Island was sometimes lonely for its several thousand residents. A few of the WAVES couldn’t cope with the dreary desolation and long periods of grim solitude. They were allowed to leave.

“Yeah, I got lonely,” Shelley recalls. But she stayed. Shelley believes she made it due to the support and camaraderie of her fellow WAVES.

“I had companionship,” she says. “Good people to talk to. We could just sit down in the lounge, have beers and complain. We disagreed on some things. But we had more in common. How bad the weather was. How difficult it was to live there.”

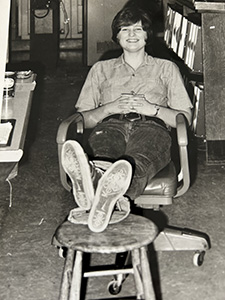

And Shelley had something else. An unexpected new job that literally changed her life. She began her tour of duty on Adak Island doing jobs that needed doing, including cleaning barracks. One day that suddenly changed. She was walking through the tunnel that connected a huge barracks to another structure, the Bering Building.

“I came out in the basement there,” she says. “I looked down the hallway. There were two swinging doors on my left. There was a sign that said Armed Forces Radio and Television Service. I was sick of barracks duty. So I walked through those doors.”

That’s where she met Petty Officer Dick Harrelson. Shelley had experienced some difficult moments with men on the island.

“Some of them made comments about your body,” she recalls. “Or asked what were we doing there? Why are you here? Snide comments. We just dealt with it.”

Shelley calls Petty Officer Harrelson “the one person who decided to give me a chance.”

He ran Armed Forces Radio and Television on the island, and he was glad to see a woman volunteering to help. He put her to work immediately. She quickly learned all the technical, behind-the-scenes jobs it took to air radio and TV programs. How to operate the control room consoles, and film and slide projectors. How to set up the studios and operate the two cameras. She loved it.

“I felt as though I had found a niche,” she says. “Like this is the direction I was supposed to go.”

Harrelson had even more in mind. Before she knew it Shelley was the disc jockey of a weekly radio show that aired after the news.

“We did requests,” she says. “My show was oldies and rock. The latest and the greatest. I was always trying to keep up on the Top 20 in the States.”

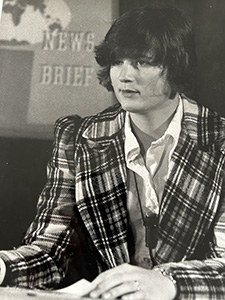

Harrelson was also looking for a newscaster to deliver the island’s television broadcasts. Shelley eventually anchored 30-minute newscasts at noon, five and six o’clock.

“I really had to practice,” she says. “I would say all the words correctly in my head but when the camera—that one-eyed monster—was staring at me I’ll be doggone if there were some words, like Syria, I could not pronounce.”

The exposure made her an island celebrity.

“Once I was standing in line at the PX,” she remembers. “There was a child in front of me. She said ‘Look mommy, there’s the lady who’s on TV!’”

Shelley and her colleagues took their jobs as journalists very seriously. Navy, Marine and Coast Guard personnel and some of their families were a long way from home. They were hungry for information. The newscasts were an important lifeline to the outside world. The reports had to be timely and accurate. The presentations flawless.

President Richard Nixon’s resignation in August, 1974, and the fall of Saigon in April, 1975, were the biggest stories Shelley reported. The story from Vietnam was especially important to the military personnel on Adak Island.

Shelley remembers talking on the phone to an airman at Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage when the bells went off on his teletype machine. That meant breaking news. He breathlessly told her Saigon was falling. Shelley hung up and went into action.

“I whipped off the copy from my teletype, called Washington from the radio room and started downloading the latest reports coming out of Saigon,” she says.

Speed was crucial. There was a lot to do for their small group of journalists. Get a handle on reliable information on a story that was changing by the minute. And monitor audio feeds and record eyewitness radio accounts from Saigon of the danger, chaos and terror.

Then they had to write scripts, coordinate them with the radio reports they were using from the scene, and make sure everyone at the station was ready to execute the plan live on the air. Shelly and her crew faced an additional obstacle for a TV news broadcast. There was no satellite service over Alaska. They couldn’t get video of what was happening. They had to make the story come alive with audio from reporters on the scene and still pictures.

“It was a hot day for us. Oh my God, I couldn’t believe it,” Shelley says. “We had to use our imaginations since we couldn’t see the helicopter rescues and Saigon being overrun.

“We would set up the story and then go from one radio report to another as they described the scene from different locations in Vietnam.

“It was extremely dramatic. There was one woman journalist. You could hear the bombs going off in the background. It makes my adrenaline boil just to think about it,” she says.

Shelley and her colleagues also took in feeds from Washington with the latest information and reaction from the government.

Her audience included men who had served in Vietnam and knew people caught in the maelstrom of the final hours. There were even listeners who had been on the U.S.S Pueblo, a spy ship that North Korea had attacked and captured in an international incident that made headlines in 1967.

“So this meant a lot,” Shelley notes. “To get the story out to them from Saigon and Washington was a great coup.”

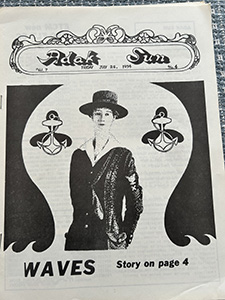

She also covered local news and information. She helped produce a newsletter called the Adak Sun. It covered Navy news and everything from news-you-could-use to survive a storm, and safety tips for hiking and swimming to features and the daily television listings. Shelley had a column on pop music.

She earned a journalist ranking during her 20 months there and passed the exam for Petty Officer. She loved the work so much she would gladly have continued. But just as bad luck kept her from an assignment as a medical corpsman, the Navy again told her there were no journalism spots available for her. So she left the Navy after her enlistment ended in 1976.

“I didn’t like the way that turned out,” she says. “But for the most part I was happy in the end because I actually got a skill I could use on the outside.”

Her knack with the technical side of broadcasting on Adak Island helped her land and thrive in jobs with AT&T in Chicago.

“I have to say that we were definitely involved in building the backbone of the internet in the City of Chicago,” she says.

Shelley’s father was happy with the life she made for herself.

“He came around,” she smiles. “By the time I got out and went to the phone company he was very proud.”

Shelley’s story is one of taking chances and responding to obstacles with creativity and flexibility. She thinks she comes by those traits naturally.

“I call myself hearty, from good New England stock,” she says. “I was raised to roll with the punches because there might not always be someone there to help pick you up.”

But she says her career showed her something else: “You get a lot of help from people. You don’t do it yourself. I got breaks. And one person decided to give me a chance.”

In fact, that’s why she’s looking forward to her Honor Flight. Her spouse encouraged Shelley to apply for the trip after they heard about it during a Walter E. Smithe commercial on TV.

“I really want to go and hear the stories other people have about their experiences,” she says.

Thank you for your service, Shelley.

Here’s hoping you have a great trip full of wonderful memories.