Navy Korea Mount Prospect, IL Flight date: 06/15/22

By David Adams, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

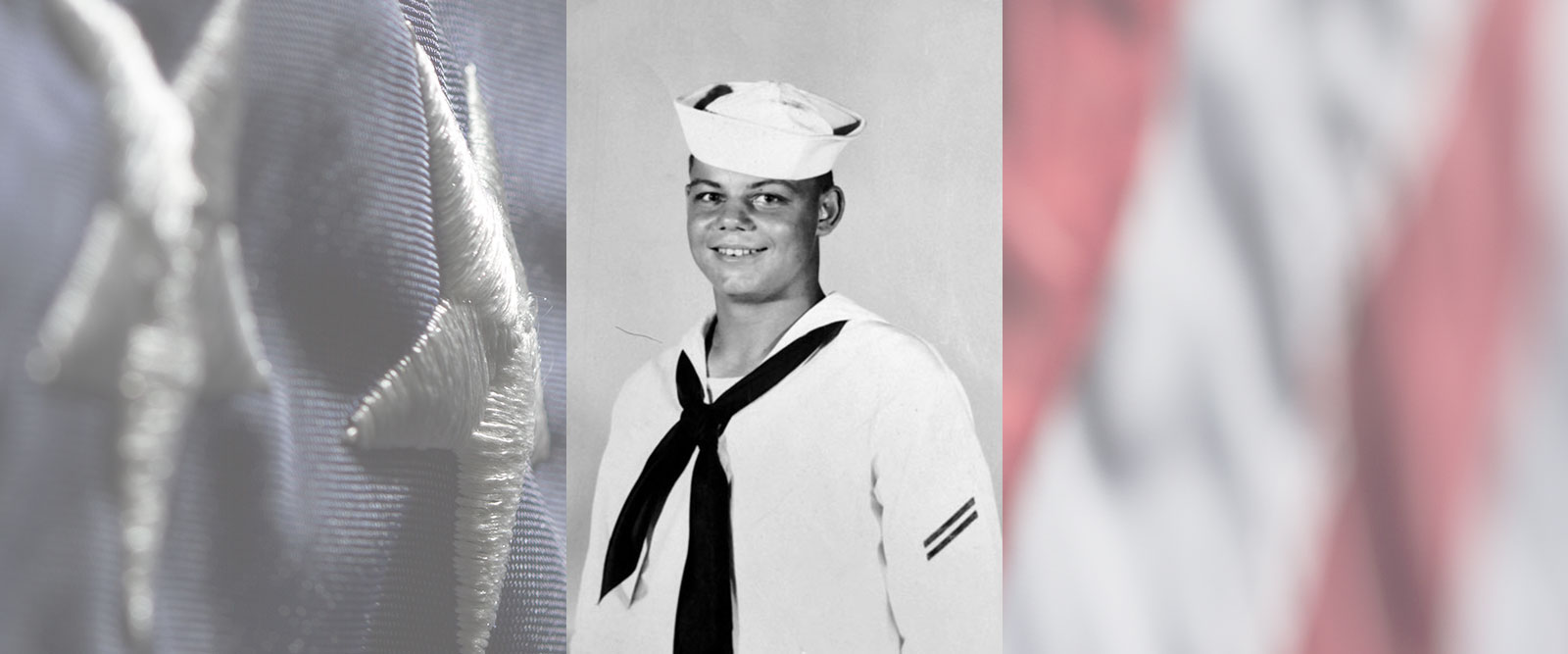

Ron was born on a farm near Freeport, Illinois in 1936, one of six kids. He began his Naval service at age 17 on May 25, 1954. He and several buddies from his neighborhood in Freeport left high school halfway through senior year to sign up for the military. Ron chose the Navy. He attended the Navy’s “Boot Camp” at Great Lakes Training Center. He thought that all four weeks were great. Next, he completed the Navy’s three-month-long aviation prep school at Norman, Oklahoma. He has always wondered why the Navy would have school in the heart of the Great Plains! His final training was “A School” at Jacksonville, FL. There he learned the ropes to qualify as an Aviation Electrician’s Mate. He became responsible for aircraft electrical power generating and converting systems. He would also maintain lighting, control, and indicating systems and could install, as well as maintain, flight and engine instrument systems. In practice, as a flight crew member, he did much much more.

In May 1955, after a year of training, Ron was assigned to VP-50 which he joined at Alameda, California. Ron learned that VP-50 was a long-lived Patrol Squadron established in 1946 and nicknamed the Blue Dragons. At first, he worked in the squadron electronics shop before being assigned to a flight crew. At the time, VP-50 flew the Martin PBM “Mariner,” a twin-engine patrol bomber flying boat which first entered service during World War II. The Mariner continued in the Navy’s inventory until 1956. Manned by a crew of seven, it could carry 4,000 pounds of bombs or depth charges or two Mark 13 torpedoes. The airplane mounted 50 caliber machine guns in the nose turret, waist turrets, and tail turret. Ron as well as the other crew members were fully qualified to man these weapons. He had a lot of practice with the 50 cals but never fired them in anger.

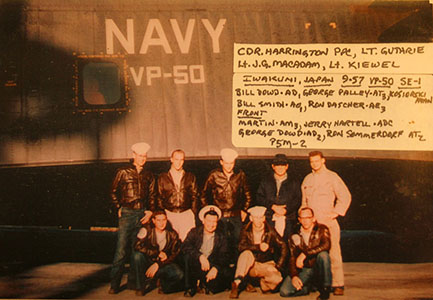

All ten of the squadron’s PBM’s deployed to Japan from California in November, 1956. He remarks that the PBM could stay airborne for about 20-21 hours. At the PBM’s speed, and accounting for headwinds when flying west across the Pacific, the squadron flew many legs with the first stop in Hawaii. Since Ron was working in the shop and not assigned to an aircrew yet, he had to spend about a month on Oahu which allowed him to enjoy this tropical paradise and see all the sights. On this deployment the squadron flew from California to Hawaii, then Johnson Island, Midway Island, Kwajalein Atoll, and onto Guam and finally Iwakuni. After this lengthy trip across the Pacific, the squadron set up operations for its six-month deployment at Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Iwakuni, Japan.

At Iwakuni, the squadron lived in WWII Japanese barracks known as the “kamikaze barracks.” Gratefully, Ron and his squadron mates made no one-way missions from Iwakuni. Also on the airfield grounds were various shrines, one of which was to kamikaze pilots. The Japanese girls gave Ron the nickname “Babyson” because according to them “I looked so young.” No one would dispute that! Since Iwakuni is located near the southwestern tip of Honshu, Ron took full advantage of visiting the sights like Tokyo, Mount Fuji, and others. If Ron didn’t go see them, they weren’t worth a visit.

While stationed at Iwakuni during this his first deployment with VP-50, the Navy decided to “mothball” the squadron’s PBM Mariners and replace them with the new P5M-2 Marlin seaplane. VP-50 was the last active duty Navy squadron to fly the airplane. Upon completion of the transition in 1956, Ron recounts that the squadron’s permanent home port was changed to NAS Whidbey Island, Washington. The squadron flew back in the PBMs and transitioned into the P5M-2 with its larger crew complement, more robust systems, and armament. The Marlin had better engines, an improved hull, and a single vertical fin tail. It carried a crew of eleven or more, was faster, and had essentially the same weapons capability as the PBM. It was also equipped with ECM (electronic countermeasures) equipment. On each mission, crew members took 20-minute shifts monitoring the scope for indications that Russian or Chinese radars were “painting” the airplane. Because of mission length, up to 12 hours in flight, the crew cooked their own hot meals. Ron remembers one of the three meals was packaged and eaten cold and the other two cooked and served hot.

On every patrol mission when a ship was picked up on the airplane’s radar, the crew descended from altitude to essentially wavetop height for a single pass by the ship. A series of photos was taken for later intelligence analysis. Of importance to the Navy were the number of exhaust stacks representing engines capability, on-deck cargo, armament (guns), bow and stern construction, flags being flown, and how it rode in the water (low meant a full load of cargo). The goal of the flyby was to take three photos or more.

Ron eventually was assigned to flight crew #1 which was commanded by the squadron skipper. As a flight crew member on “1 boat” in squadron slang, certain benefits accrued. For example, the “boat” was not required to anchor to a buoy out in the water with the crew transferring to the beach via a real boat. Rather the “boat” was towed up onto the shore. Ron and his crewmates then jumped onto the sand without getting their feet wet. He stayed with “1 boat” until his discharge in November, 1957. VP-50 deployed twice to Iwakuni and once to Guam during Ron’s service. Missions out of Iwakuni were conducted off the coasts of the South China Sea and Yellow Sea where the patrol airplanes searched for submarines and cargo ships. Missions from Guam involved searching the very busy commercial sea lanes for Russian ships.

Ron received his Honorable Discharge in November, 1957 with the rate of AE3, Aviation Electrician’s Mate Third Class. He went back to Freeport where he held a variety of jobs. He soon took advantage of the GI Bill enrolling in the Northrop Institute of Technology in Inglewood, California. There he obtained his A&P license. Back in Illinois, he was hired as a mechanic at Rockford Airport. After a couple of years at Rockford, Ron broadened his horizons and began working at O’Hare as a mechanic for Eastern Airlines. He worked 25 years for Eastern where he became lead mechanic-then moved on to American Airlines for 15 years where he ran the avionics shop. Following his retirement in 2005 from his 40-year-long “day job” with the commercial airlines, Ron stayed very active. From 2007 to 2017 he volunteered as Chief Engineer with the Marine Navigation Training Association in Chicago. He taught engine room operations and repairs. Among his many students were Navy sea cadets. Ron has been honored repeatedly for his work and volunteer efforts including especially by the FAA and the Chicago Chapter of Professional Aviation Maintenance Association, earning the “Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award” for his technical expertise, professionalism, and contributions to aviation safety.

Ron met his wife Patricia in their hometown of Freeport after his discharge from the Navy. At first, he thought she was too young for him, but this quickly turned into a lifelong partnership. They had been married 56 years at her passing last year on Valentine’s Day. They have one son who is a private pilot, an A&P mechanic like his dad, and works at O’Hare. Like father, like son!

Remarking on his three and a half years in the Navy, Ron says, “I had a good time in the service. To this day I wonder why I got out.” Regardless, Ron, we are glad you did contribute to the defense of our country during turbulent times and embarked on a distinguished aviation career.

Thank you, Ron, for your dedication and extraordinary service. Enjoy your special day of honor in Washington D.C. with your comrades in arms! This will surely be a splendid welcome home and one more safe landing!