Air Force Vietnam War Wheeling, IL Flight date: 08/24/22

By Wendy L. Ellis, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

It was 1966. His student deferment was gone, and his draft papers had arrived. For Rick Ellish it was a chance to follow in his father’s footsteps. His father was a lifer in the U.S. Army infantry. He fought at the end of World War II and served in Korea. But when Rick gave his dad the news that he’d been drafted, the reaction wasn’t what he expected.

“I told him, ‘I want to be a gunner on a Huey. I’m gonna join the first Cav,’ and he said, ‘No, no you’re not gonna do that.’ And he drug me by the earlobe and got me to the Air Force recruiter in Arlington Heights, and said, ‘You’re gonna go into the Air Force. You’re not gonna get shot down in the first 20 minutes.’” It was the beginning of a successful four years in the military that was marked by several Airmen of the Month awards, a Meritorious Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal and the National Defense Medal. In other words, Rick Ellish was good at his job.

Rick’s time in the Air Force didn’t really start out the way he hoped. After Basic Training, he was sent to Keesler AFB in Mississippi and assigned to run the base mess hall. “I didn’t cook. I was the boss. We fed 4,000 troops a day.” His efficiency won him his first Airman of the Month award, but after 8 months, he wanted more. He wanted to become a Pararescueman, rescuing pilots who got shot down. But there were no openings, so he picked the next job on the list, Life Support Specialist.

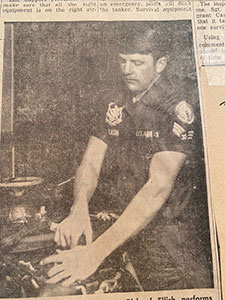

“We used to maintain all of the survival equipment that pilots and crew members used,” says Rick. “Their weapons, survival gear, strobe lights, life preserver units and rafts. We made sure they were operational so if they did get shot down, they would have all the gear ready and on them when they bailed out.” They also learned survival techniques to pass on to pilots in the field.

“In training, you get pulled out by a four engine speed boat, and then you have to release the parachute from the boat itself. Then you sail down and the chute drops on top of you and you have to get yourself out from under. I used my life preservers and wiggled my way out from under.” Teaching pilots what to do after they’re shot down was a vital part of the job as well. “We also taught them how to use their strobe lights and when to use them. Once they got shot down, you had to do everything you could to save them. Otherwise they’d be dead or sent to the Hanoi Hilton.”

Rick was posted to Kincheloe AFB in Michigan’s UP for 18 months before he finally went to his commanding officer and volunteered to go to Vietnam where his skills were needed. And so it was that he traded the ice and snow of the Upper Peninsula for the jungles of Southeast Asia. It was June of 1969, and he was posted to Ubon Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand, supporting the 25th Tactical Fighter Squadron. The four Life Support Specialists in his unit took care of roughly 30 pilots and navigators. “Our squadron delivered laser guided bombs, so those guys had to be pretty sharp,” says Rick. They also worked the flight line, removing parachutes from the airplane, working round the clock, since sorties were going out constantly. Each specialist wore a patch with the unit’s slogan, “Your Life is Our Business.”

Although he spent most of his time on the ground, Rick had some memorable moments in the air. His commanding officer let him assist gunners on more than a half dozen flights into Cambodia and Laos. Sitting next to the gunnery officers , he would scoop away the hot brass and clear jams, as the gunners fired at supply lines below. Then, after getting another Airman of the Month award, he won a hop on an F-4 Phantom coming out of phase.

“I wanted to jump into the back of one of those F-4 phantoms that I worked on everyday,” says Rick “After so many hours they have to put it through its paces. Capt. Schwartz air rolled that thing. To me it was like going straight up, but he had an angle. You pull the G’s, your G suit inflates. It was awesome.”

As his time approached to return to the states, the Air Force offered him some hefty incentives to stay in and make a career of the military, as his father had done. But in the end, Rick opted to rejoin civilian life. He worked in the telecommunications industry as an outdoor lineman, cable repairman, an engineer planner and a manager, jobs that spanned over 40 years until his retirement. He and his wife Cheryl will celebrate 50 years of marriage in November. They raised three children and enjoy their 8 grandchildren. And to stay useful, Rick drives autistic children to and from school each day for Chain O’Lakes Transportation.

During his time in Thailand, Rick only lost one pilot, a good friend. The pilot suffered a case of vertigo while on a mission and ejected upside down. Although his navigator returned safely, his friend did not. “I hope to get a rubbing of his name from the wall when we’re in Washington,” says Rick. Although he’s seen the traveling wall several times, he has never seen the real Vietnam Veteran Memorial. That will soon change. Although he didn’t become a lifer like his dad, it is clear Rick is proud of the work he did while in uniform.

“Were we shot at every day? Yeah. Were we hit? Yeah. But I thought it was a great experience. I think I got a lot of regimentation out of it. My dad loved the Army. I’m kind of glad he had dragged me to the Air Force recruiter.”

So are we, Rick Ellish. So are we.

Thank you for your courageous efforts as a life support specialist in service to your country. Enjoy your well-deserved day of honor on Honor Flight Chicago’s 104th mission!