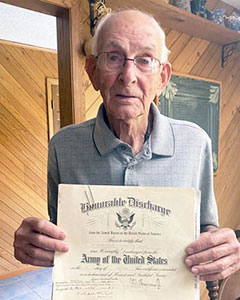

Army Korean War Roscoe, IL Flight date: 06/19/24

By Wendy L. Ellis, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Lessons learned in a war zone can last you a lifetime, assuming you make it home alive. Sergeant Dick Hanson learned quickly that taking pictures from the turret of a tank on the front lines of Korea can get you killed.

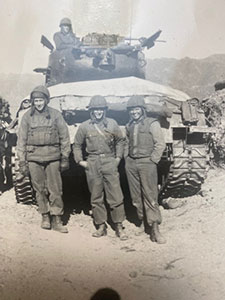

“Remember the old box camera that you look down on,” says Hanson. “The tank commander opened up the door at the top of our tank, and I went up there and I’m standing up there looking down, taking a picture and ‘ping, ping’. A sniper was shooting at me. Just by my ear. That was the end of that. I learned my lesson.” While that may be one picture Hanson didn’t get, his collection of old black and white photos from his two years in Korea covers his tabletop and fills photo albums. They are as prolific as his memories.

Hanson grew up on a farm in Roscoe, IL, with his mother and older brother, where they worked for room and board. The farm had no running water, and no electricity, not even a tractor, just horses. Graduating from high school in 1950, he went to work as a truck mechanic at the Sunbeam Bakery until he was drafted in 1951. Six weeks of infantry training and six weeks of Tank training at Fort Knox preceded his assignment to the 279th tank company in Oklahoma.

“I knew where I was going,” says Hanson. “But at least I got off the farm.”

Barely 20 years old, he had seen little of the world before being shipped to Korea. They arrived near the 38th parallel at night, but he saw not much of his surroundings. He was running a 105 fever and was sent directly to a hospital in Seoul. “I remember, I looked up and it had no roof,” says Hanson “It had been hit.” By the time he was well enough to leave the hospital, his job as a tank mechanic had been given to someone else, and he was reassigned as an assistant tank driver. Fortunately, he knew how to handle the sticks. Hidden among his photographs is his tank driver’s license.

The tank he called home in Korea was a Sherman M4, the same model Patton used in World War II. One of a five-man crew, he said many a foot soldier climbed on board to hitch a ride whenever they passed by. “Sometimes there were so many I could hardly see.” Eventually the tank driver went home, and Hanson moved up to be the driver, renaming the tank Big Dick’s and reaching the rank of Sergeant. About a month would be spent on the front lines with a dozen or more other tanks. They lined up along the 38th parallel, guns aimed at the other side, where the North Koreans and Chinese were equipped with Russian tanks. “We could hear them using their artillery, but we couldn’t see them,” says Hanson. “The Russian tanks were too big for the roads there.” On more than one occasion, the US tanks would hold a Turkey Shoot. “Everybody on the front lines would line up and all fire at once,” says Hanson. “Just shoot, shoot, shoot. With everybody shooting it was massive shells going off.”

At night at least one of the crew, usually the gunner, would have to stay in the tank, “just in case.” The others slept in a makeshift hooch behind the tank made with sandbags. “One morning we got up and found three dead Chinese soldiers in front of our tank.” We never heard a thing. I have no idea who shot them.” There are photos of that, too.

Hanson says they would stay at the front line for about a month, before heading back to the reserve area to clean the tank, do any necessary maintenance, and generally get some R & R.

It was there, along the Han River, that he remembers one of the saddest moments of his time in Korea. The rains had been falling steadily, and his crew decided to move his tank away from the river’s edge while they cleaned it because of softening sands. Meanwhile, Easy Company was camped across the River, and had built an inflatable bridge for their men to cross.

“They all had their ponchos on and weapons, and they got onto that rubber bridge and it tipped. It was like a flood, the water just tipped them over,” says Hanson. “Thirty guys drowned. And we were standing there watching and there wasn’t a thing we could do. They were just trying to get back to their camp. That was a sad day.”

Hanson says some of his high school friends had joined up before him, believing that with the end of the Second World War, the worst was over. But they were assigned to the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea, which became one of the worst battles of the Korean War. Some of them made it home, some didn’t. Hanson considers himself one of the lucky ones, even though they always had to carry a gun, even when they slept. He has not touched a gun since.

Hanson returned to the US in 1953 and was hired on as an electrician at Ingersol for 95 cents an hour-although his electrical knowledge was self-taught. “After the war they had started bringing electricity to the farmers,” says Hanson. “They stuck an electric pole in the middle of the field and the farmer hired a guy to wire the house. He paid him up front and he drank it up and never finished. So I thought, I know how to do this. The wires were hanging all over. The electric company had already brought the wires to the box so I was working on the wires and screwed in a light bulb and it came on. I didnt know the power was on!”

He finished the whole house and ran the wires to the barn. So when the Ingersol interviewer asked if he knew anything about electricity he said yes! That led to a 38-year career with Ingersol, traveling all over the world to keep assembly lines at auto plants working. Hanson married and had three children along the way, but his memories of Korea are still very fresh, brought to life in the black and white photographs of a time gone by, but not forgotten.

Thank you Sergeant Dick Hanson, for your service!