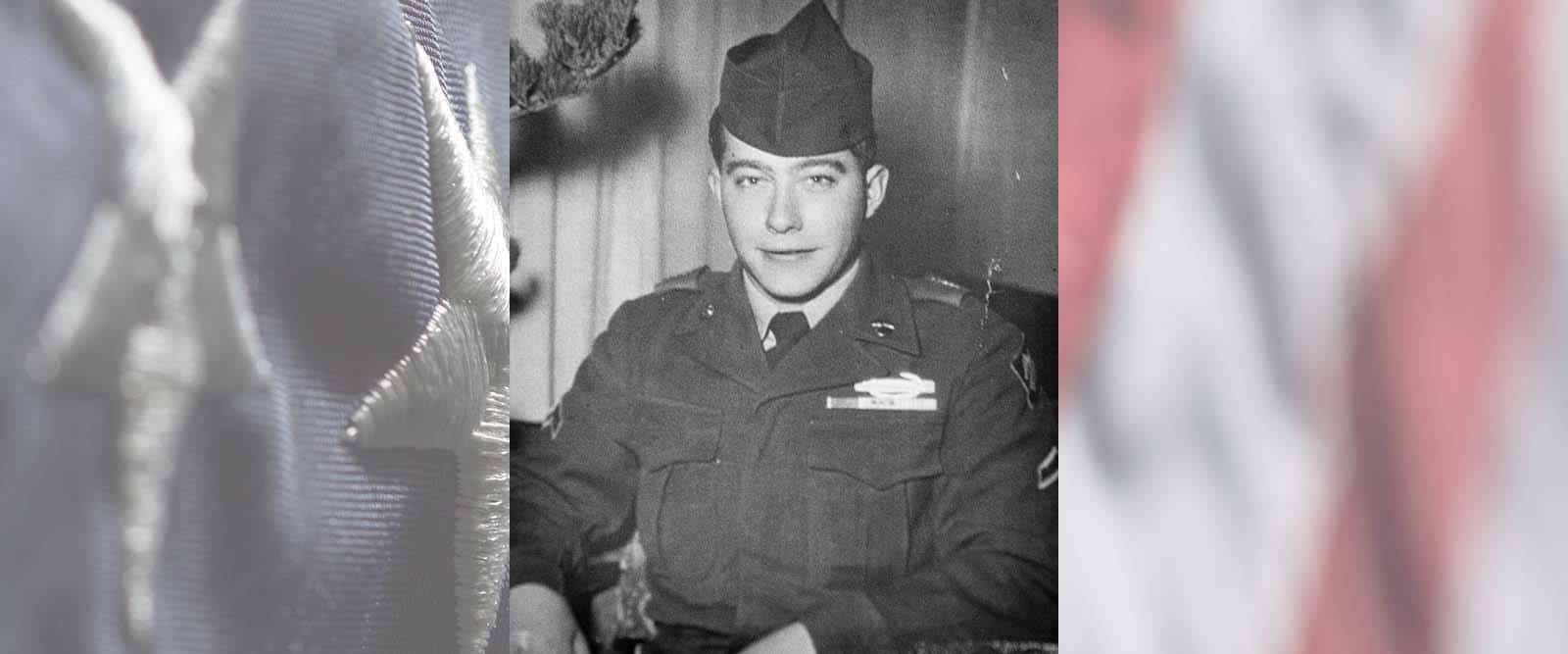

U.S. Army Korean War Zion, IL Flight date: 07/12/17

By Jack Walsh, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Pete Balma was very happy when his time in Korea was over. He was there for 14 months, and they were 14 hard months. It all began when he was drafted at the age of 21. He had just gotten married in July 1951, but in January 1952 he was inducted into the US Army in Chicago.

He was born in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, in Calumet, which is in the heart of Copper Country. “The weather is cold up there – they had 255” of snow this year. As we used to say, we had 8 months of winter and 4 months of bad sledding.” Very quickly he realized that copper mining wasn’t for him, and at age 17 he moved to Chicago to find work. Pete was helping to make tractor parts for the military when he was drafted.

Soon, Pete was off to Camp Roberts in San Miguel, California for 16 weeks of Basic and Advanced Infantry Training. As an infantry rifleman, he was shipped out of Oakland on a troopship to Yokohama, Japan, and then on to Inchon, Korea. He joined the 45th Division, 279th Regiment, Company K. “I was assigned to the Chorwon Valley Sector. My main mission was just to stay alive.”

When Pete’s division arrived in Korea, fierce fighting was still going on, back and forth for inches of ground. At one point, they crossed the Inchon River, but eventually fell back and established the 38th Parallel as the MLR – Main Line of Resistance.

“My job was to do contact patrols, and then call in the artillery. They would try to wipe (the enemy) out, and they did a pretty good job. I would give them coordinates, and they were accurate. The enemy would go hide into the sides of the mountain, so the planes had a hard time finding them.”

“North Korean soldiers tried not to take prisoners, and they would kill most of the prisoners they did take. We had a lot of guys captured, and we never saw them again. Just before the war ended, we had a Chinese division positioned in front of us, but we had no problem. In fact, just before Christmas, the Chinese sent back three prisoners to the company commander as a Christmas present. It was kind of neat. We would talk back and forth with the Chinese, and we had an understanding that we wouldn’t shoot each other. “

“We would go up on the line for 30 to 35 days and then come back to the camp for a week. The longest time I spent on the line was 41 days. The weather conditions were unbelievable – bitter cold in the winter, and in the monsoon season, it would never stop raining. Not a hard rain, but a constant drizzle.”

“We always knew when we were going to get a hot meal. The Navy would fly over and drop napalm in front us. We thought ‘Oh boy, we’re getting a hot meal’, and sure enough we got it. We got real tired of eating C-rations.”

“I remember the time we were putting a guy on a litter onto a jeep, and a mortar round came in and landed on the console gear shift of the jeep. Fortunately, the round was a dud, or we would all have been dead.”

“When we were up on the line (MLR), we had a flag that we would turn a specific way each day. That way, the planes flying above would know that we hadn’t been overrun, and that we were below. Well, one day somebody above misread that flag, and we started thinking ‘Boy, those bombs are coming close’. Suddenly, I was on the radio, screaming….”

It wasn’t long before Pete became a squad leader, and he eventually wound up as the platoon sergeant, with about 40 troops under his command. The skills he developed while growing up-hunting, reading maps and surviving when it’s rough, served him well throughout his army career.

“To rotate out of Korea, you needed 36 points; you earned 4 points a month. But that didn’t work for me, because they froze my rank (Sergeant), and I had to stay. I was there 14 months, until the end of fighting after the armistice.”

“A friend and I had made a pact, that if one of us got killed, the other would go visit his parents. Well, he was from the Yakima Valley in Washington, and he got killed. The hardest thing I’ve ever had to do was to go see his parents. They knew he was gone, but I had to go visit them. They were great — even offered me a job in the orchard they owned so I’d stay, but I had to get back to my wife in Chicago.”

In October 1953, Pete was sent home and discharged at Ft Riley, Kansas as an E-6. He reunited with his family back home in Chicago. It wasn’t easy to get on with life. Today it would be called PTSD, but back then it was called “battle fatigue”, and Pete had to deal with it. He says it took more than 8 months for it to start to fade. “You can’t imagine what it’s like, scared during the night, looking out the windows, having flashbacks.” Even today, Pete doesn’t watch any war movies to avoid having bad dreams all night.

After the war, Pete did manage to rebuild his life. He had 5 children, and today has 10 grandchildren and even 4 great-grandchildren! All of them are still in the Chicago area. He was plant manager for a manufacturing company for many years, but finally was able to retire at age 68. He really enjoys traveling around the world, and continues his life-long passion for fishing and hunting.

Pete Balma, thank you for your service and enjoy your day of Honor with your fellow Korean War veterans.