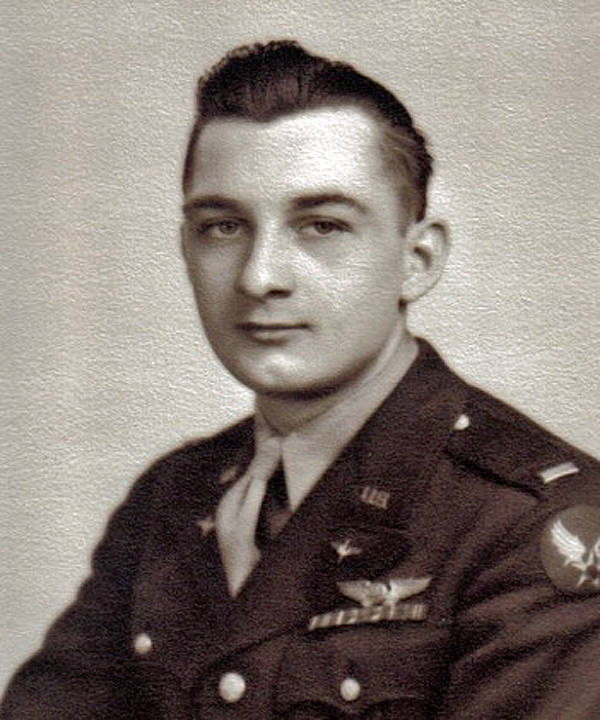

U.S. Army Air Forces World War II Pingree Grove, IL Flight date: April, 2019

By Jim Parker, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

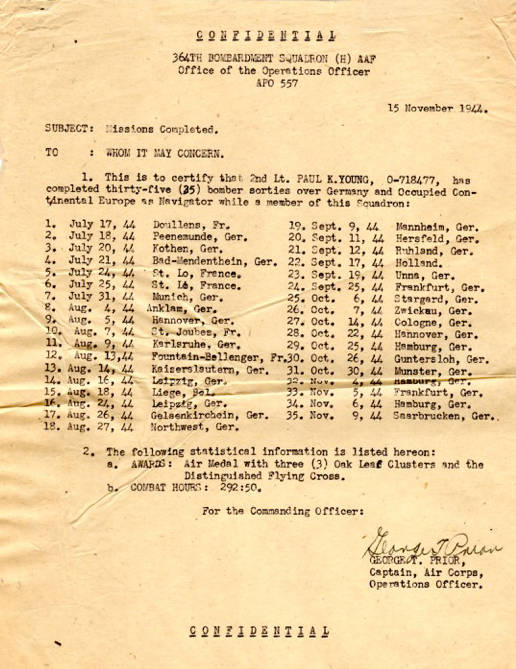

In most lifetimes, 116 days is not a particularly long time. It’s less than a school semester and a little bit more than half a baseball season. For Paul Young it was long enough to fly 35 missions over hostile territory as a B-17 Navigator in the middle of World War II, accumulating over 700 flying hours, 300 of which were considered “combat hours.” And it was long enough to make a significant contribution to his country, earning the right to be called a hero.

Paul was born in Pittsburgh on April 13, 1921. His father was a superintendent at a local steel mill. Sadly, he passed away when Paul was only three-years-old, leaving his mother to raise Paul and his older brother, William, by herself. She opened a small confectionary store to help pay the bills during the difficult Great Depression years.

Paul’s mother eventually remarried and Paul’s half brother, Don, was added to the family. When Paul was 10, he met a young lady named Norma in Sunday school and stayed in touch with her through high school. She became (and remains) the love of his life. After graduating from high school in 1938, Paul went to work at the Royal Typewriter Company where he did local deliveries and repair work. Later he took a job with the federal government. The Flood Control Act of 1938 created thousands of jobs during the Depression by constructing many dams and lakes to help with flood control. One of these projects was the Berlin Dam to be located in nearby Portage County, Ohio. Paul went to work in the legal department of the Pittsburgh District helping with deeds and other documents needed to acquire the hundreds of parcels of real property that made up the 8,000-acre project area. He enjoyed this work and learned the importance of organization and attention to detail.

In 1941, Pearl Harbor changed his life as it did for all young men in America. Faced with required military service, his Mom showed him a newspaper article about a test to be given by the War Department to identify candidates for flight crew training in the US Army Air Forces (“USAAF”). Paul took the test with 250 other applicants; he was one of only 18 men to pass it. In the summer of 1942, Paul was officially sworn in but was not required to report for his pre-flight training until March, 1943. His actual pilot training followed in Avon Park, Florida. Paul was a good student and soon flew his first solo flight in a training aircraft before he had graduated from flight school. During a routine training flight, Paul low on fuel, encountered another airplane that had made an incorrect approach. Paul gave him a “wing waggle” to draw the pilot’s attention to Paul’s low fuel condition and that Paul needed to supersede the normal landing order. Unfortunately, that other pilot was in the process of a “check flight” from an instructor who did not take kindly to Paul’s action. Later on, the instructor told Paul that he would have to take a special “check flight” and pass it in order to remain in pilot training. Paul knew exactly what that meant. No matter how well he flew, enough mistakes would be found to cause Paul to be “washed out.” That is exactly what happened. Unable to change the results of the check flight, Paul’s commander offered Paul his choice of any other MOS (job classification) in the entire Army Air Force. Paul could have selected a cushy, non-combat job as a supply officer or something similar but instead chose to attend Navigator School. This turned out to be a good decision — both for Paul and for the USAAF.

Paul reported for his navigator training in Monroe, Louisiana. With his pilot training, natural intelligence, and eye for detailed analysis, Paul graduated from the 18-week program with very high scores. However, Paul did have a potential problem since he and Norma planned to marry during a leave that he was expecting to receive after finishing Navigator School. By this time, the air war in Europe was heating up and the USAAF found itself with a shortage of trained navigators. The USAAF decided that only the top 25 graduates would be allowed to go on leave. Paul knew his grades were good, but he did not like his chances, as there were over 400 men in his class. He was afraid he would have to call Norma and postpone their wedding. When class rankings were announced, Paul had finished at number 17. He did not have to make that call to Norma! On April 14, 1944, they were married in a suburb of Pittsburgh.

After a short weekend honeymoon, Paul reported to Sioux City, Iowa, where he met his B-17 flight crew. They were assigned a new plane and ordered to England. This was a long flight with a stop in Newfoundland and the longest leg of the flight was to Ireland. Paul set his radio compass to the required heading, gave the information to the pilot and settled in for the flight. But soon, his navigation skills would face a challenging test. They were flying between two very thick cloud layers so neither he nor the pilot could see the sky above them or the water below. It was at this time that the radio compass failed. Unable to use celestial navigation, Paul’s only tools to keep the flight on course were the weather information he had gathered in Newfoundland, his maps and dead reckoning. After some tense hours, Paul calculated that they must be near Ireland. It was then the radio compass started working and he found that the needle was pointing to zero – Paul had managed to keep the plane exactly on course! Without much further difficulty, the crew arrived at Nutt’s Corner, Ireland, then went by boat and train to their new home in Chelveston, England.

They were assigned to the 305th Bombardment Group (Heavy), one of the oldest and most highly decorated bomber groups in Europe. By the time Paul arrived in July, the 305th already had two Unit Citations and two Medal of Honor pilots. It also had a very high casualty rate and the required number of missions for a complete tour had been raised from 25 to 35. Its mission was daytime strategic bombing of manufacturing centers, transportation facilities, marshalling yards and major cities in Germany and occupied countries in Europe. Under its first Commander, Col. (later General) Curtis LeMay, the group pioneered many of the bomber formations and procedures that became standard in USAAF operations. A typical mission was 8-to-10 hours in total flight time. Much of that was spent over heavily defended target areas. Those defenses included enemy fighter planes and something the Germans called “Fliegerabwehrkanone” meaning “pilot warding-off cannon.” Our guys nicknamed it flak. Earlier missions’ losses were very high because the USAAF underestimated the German defensive capabilities.

Paul’s first mission was on July 17 to a target near the Pas-de-Calais in France. The next day was his second mission to Peenemunde in Germany, the location of the testing and production facilities for the V-1 and V-2 rockets. Paul flew five missions his first week. One of those was near the French city of Caen – “the heaviest flak I ever saw.” His 6th and 7th missions were in support of Operation Cobra over Saint-Lo, France. That was General Omar Bradley’s operation that resulted in American ground forces finally breaking out of the hedgerow country after D-Day. Paul’s 8th mission was to Munich, Germany. Directly over the target, the flak was extremely heavy and the plane took damage. One piece of high velocity flak caught their top Turret Gunner and Aerial Engineer behind his left ear, instantly killing him.

Later, one of Paul’s missions found him over Holland, bombing German anti-aircraft installations in support of the ill-fated British Operation Market Garden. During one mission near Berlin, his squadron was in the midst of many German fighters. From his position just behind and to the right of the Bombardier, Paul saw four B-17s get shot down. Paul fired a machine gun at a fast approaching German plane and put it on the ground. On another mission, Paul’s plane was in the middle of a very dense concentration of flak. A shell exploded directly under his plane sending many pieces of shrapnel into the plane. One piece cut through his flight suit and ripped off the toe of his boot. Miraculously, Paul’s body was not hit, but he had to unplug the electrically heated flight suit as the flak had shorted it, causing it to catch fire. With a -60F temperature in the plane, his return to the base seemed to last forever. He feared flak more than the enemy fighter planes.

On October 7, 1944, the target was Zwickau, an important industrial site in Germany. During the post mission debriefing, Paul learned that he was the only navigator in the formation to correctly locate the bomb damage. Paul was immediately offered the position of Lead Navigator for the Group and with it, a promotion to First Lieutenant. Earlier in the week, Paul had learned that Norma was pregnant with their first child and he wanted to complete his 35 missions and go home. Because the Lead Navigator flew fewer missions per week than other navigators, the promotion meant that it would take Paul a much longer time to reach his goal, so he turned it down.

One of Paul’s most frightening missions did not involve fighters or flak. It was over the Saarbrucken marshalling yards on November 9, 1944. Paul was assigned to fly with an inexperienced flight crew. A “very green” pilot was flying the plane and flew to the rendezvous point at full throttle, not leaning the fuel mixture after takeoff. This used a large amount of fuel unnecessarily. Paul alerted the pilot that doing this could make it unlikely that they would have enough for the flight home, but his advice was ignored. After the bombing run was completed, Paul’s fears about fuel consumption were confirmed. As soon as the formation crossed into Allied territory, Paul told the pilot they would have to abandon the formation and fly a straight line to their base or they would not make it back. Because of the obvious dangers of flying alone, the pilot did not want to do that but changed his mind when Paul told him that staying with the formation would result in a forced landing in the English Channel. Thanks to Paul’s course, the plane made a successful landing in England, though they had lost power to three engines upon approach and lost the fourth on the runway. That mission was Paul’s 35th and last. He had completed the required number and earned a ticket home.

After some leave time, Paul’s next assignment was as a Navigation Training School instructor, where he finally received his promotion to First Lieutenant. In September 1945, he received an honorable discharge and returned to Pittsburgh. In 1950, he took a job with the Duquesne Light Company. He rose through the ranks eventually becoming the Director of Residential Services, a position he held until his retirement in 1986. Paul and Norma lived in the Pittsburgh area until August 2016 when they relocated to Pingree Grove, where they currently reside. They have three sons, Robert (deceased) who was a Captain in the Air Force, Alan and Douglas, eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. Still very much in love, Paul and Norma will celebrate their 75th wedding anniversary four days after he will be honored with his Honor Flight.