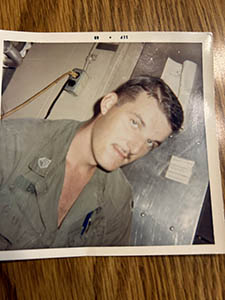

Army Vietnam War Flight date: 07/24/24

By Joe Kolina, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

A U.S. Army helicopter dangled precariously over the battlefield. Wounded soldiers needed help. Right Now. Speed was critical. But every time the pilot tried to touch down fierce enemy gunfire erupted from the thick surrounding jungle, forcing the chopper to jerk back up out of the line of fire.

Staff Sergeant Lloyd Busse watched in dismay from a sheltered perch below. He was the squad leader. He had to do something.

“It was instinct,” he says. “I had to try to protect people who depended on me.”

He grabbed an M-60 machine gun and ran headlong into the open. The M-60 was an iconic automatic weapon of the War in Vietnam, valued for its power and range. It was nicknamed “The Pig” due to its bulky size and the massive amounts of ammunition it burned through.

“I loaded up, “ Lloyd says, extending his arms out, fingers clenched as if wrapped around the M-60. He conjures up an image of Rambo, machine gun raised and ready, ammunition belts strapped across his chest. “I pulled the trigger and didn’t stop until the chopper got down. I fired so many rounds the heat started to melt the gun. The tip of the barrel was bent.”

The gun was so mangled some bureaucrat at first actually wanted to court-martial Lloyd for destroying government property. His captain and fellow soldiers put a quick end to that.

Lloyd doesn’t know how he survived 11 months of combat in Vietnam without a scratch. He shrugs with a sheepish grin when I ask. As you read more about what he did to earn two Bronze Stars, among other medals, you won’t be able to figure it out, either.

Lloyd doesn’t like to talk about combat. When he does the words come haltingly. His jaw tightens. His face flushes. His eyes moisten when he recalls fallen friends.

“Sometimes I don’t want to remember,” he says.

It’s hard to imagine the swift, drastic changes people like Lloyd experienced at a young age. In one summer an 18-year-old boy from sleepy Palatine, Illinois transformed into an 18-year-old man fighting for his life in the lethal jungles of Vietnam. In 1968, Lloyd graduated from high school, proposed to Bonnie, his one and only love, got drafted, went though basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, then completed advanced infantry school at Fort Polk in Louisiana, and finally ended up in a rice paddy 8,000 miles away in the legendary Mekong River Delta.

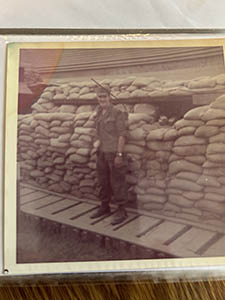

Lloyd served in the Army’s Mobile Riverine Force, 9th infantry, Company B, 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry. Soldiers launched amphibious assaults to search for Viet Cong soldiers and supplies, perform hit-and-run raids, and carry-out reconnaissance patrols.

Life in the Riverine Unit had a strange rhythm. It could go from monotonous to intense in seconds. Members of the unit lived in cramped quarters— a bunk and a locker— on board three huge Navy ships. When it was time for a patrol, they were loaded into choppers or small boats, ferried to remote locations, and dumped. They were on their own for five-to-seven days at a time.

“They didn’t land and drop you off nice and easy,” Lloyd remembers. “They slowed down long enough for you to jump out without them stopping, and away you went.”

Soldiers walked for up to nine hours every day over trails and through rivers and rice paddies ringed by nearly impenetrable bamboo jungles. It was hot and wet and treacherous.

What did he think about as he trudged forward, I ask.

Lloyd looks at Bonnie, now his wife of 54 years, and says, simply, “Her.”

But that wasn’t all. The trails were booby-trapped with mines and hidden bamboo spikes as sharp as knives.

“We encountered fire every day,” he says.” Most of the time it was a couple of guys in the jungle. They fired and ran. Sometimes there were more and that was different.”

Full-fledged firefights with large Viet Cong forces were major battles. They sometimes called for acts of extraordinary courage. Lloyd remembers one night battle that left a number of GIs wounded.

“It was so dark the medivac unit couldn’t see where to land,” Lloyd recalls. “I found a strobe light. I crawled on my belly out to the landing area in the middle of a rice paddy. I don’t know how many times I was shot at. But I finally was able to guide the chopper down and get the casualties out.”

I wonder why he didn’t just order one of his squad members to take those kinds of chances.

“I would never tell my squad to go and do something if I wouldn’t do it myself,” he says.

Most of his battles were fought against unseen foes. Bullets would suddenly whizz by as the squad walked through the jungle. They scattered, hit the ground, determined the direction of the attack, and returned fire. Once Lloyd and a couple of men crossed over a river to secure it for others to follow when a massive barrage of gunfire trapped them for a time in between American and Viet Cong forces.

“I saw two of the enemy run into the open,” he says. “It was the only time I ever saw the men I was shooting at and who were trying to shoot me.”

Battles at night and early in the morning were the most dangerous.

“That’s when they could really surprise you,” he says. “The darkness at night. And in the morning you were half-asleep.”

Lloyd remembers a squad member who fell asleep on watch duty.

“I woke him up and said what are you doing? You have to stay awake,” he says. “Well, the next morning we got attacked, and sure enough, he’s the one who got hit.”

There was nothing Lloyd could do to help him.

“I cradled him in my arms,” he says, “and cried.”

Some missions were pure frustration. Lloyd remembers a place they called Kong’s Island. They were sent there numerous times.

“Every time we went there we got hit,” he says. “I mean bad. It came to the point the captain wouldn’t tell us when we were going there. One time we literally surrounded that island with every available man from all the companies. We figured we were safe after that. Two weeks later, we went back. We weren’t.”

Lloyd came back home after serving two years in the Army. He married Bonnie and had two kids. He rejoined the custom woodworking company where he started work before he was drafted—a total of 43 years with the same company.

He’s tried to put his war years behind him. Sometimes it’s not so easy. Loud noises startle him. He avoids fireworks shows to this day.

“The first year when I was back home we went to the Palatine fireworks. We were so close,” he says. “First the loud bam, and then the smell. The smell really did it. We left.”

Lloyd’s humble about the awards he received for his Army service. A Bronze Star Medal with First Oak Leaf Cluster, a Bronze Star Medal, First Oak Leaf Cluster with V Device, the Army Commendation Medal and the Air Medal.

“I’m not one to say I did this and I did that and pat myself on the back,” Lloyd says. “I don’t feel right about that. How many guys died and I walked away without a scratch on me.”

So he was surprised when he learned that his daughter had submitted the paperwork to Honor Flight Chicago, and that he had been chosen for the upcoming July flight.

“I told her she shouldn’t have done that,” he says. “I don’t need to go. They should have given it to someone who deserves it more than me.”

Lloyd is the only one who feels that way. He epitomizes the ideal of the American citizen soldier. He answered the call, he did his duty, he put his life on the line for his country and his comrades.

He’s a hero.

Congratulations, Lloyd!