U.S. Army Vietnam War Mokena, IL Flight date: October, 2019

By Bob Pomorski, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

When you meet John Walker, he is a very warm and welcoming person. When he begrudgingly tells you about his time in Vietnam, right away you know he is one of the most courageous people you will ever meet.

John grew up in the Mt. Greenwood area of Chicago. His mother was a homemaker who also worked at Carson Pirie Scott decorating packages; his father was an auto mechanic. After years of being a mechanic, John’s dad, along with a partner, bought a Studebaker dealership and then smartly changed to a Ford dealership. There was little change going on in the Mt. Greenwood area during this time. In both grammar and high school, John had some of the same teachers that his parents had. While in high school, John was on the swim team and joined the school’s “acapella” choir.

After high school, John went to work for the Ford Motor Company, and at age 19 was drafted. He reported for the draft at the processing station in downtown Chicago. With over 500 men lined up, a Sergeant pointed at each man down the line, alternating in three groups saying, “Army – Navy – Marines.” John was delegated to the Army.

Leaving behind his complacent life on the southside of Chicago, John was sent to Ft. Leonard Wood in Missouri for eight weeks of Basic Training. John said the soldiers affectionately called it “Fort Misery” for it was an old, damp, and dreary place. The barracks had coal burning furnaces, and wouldn’t you know it, in 1965, while John was at “Fort Misery” there was a coal strike. They endured some cold nights living in those barracks. For Advanced Infantry Training, he spent another eight weeks at, you guessed it, “Fort Misery.” During this time, the soldiers took tests, and based on the results, the Army assigned the men accordingly. John tested out well, and was assigned to the 4th Infantry as a Combat Engineer.

When the orders came, John was sent to Ft. Lewis, Washington. For the next 3 – 4 months, it rained a lot. John said it felt like “monsoon training,” in preparation for what the elements would be like in Vietnam. The Combat Engineers learned how to lay roads, build bridges using corrugated metal, operate all types of vehicles, partake in explosives training, and endure more infantry training.

After getting two weeks of leave to spend time at home in Chicago, John’s division was sent to Vietnam aboard the USS Walker, no relation as John jokingly mentions. There were 5,000 men, sleeping 4 bunks high, enduring fourteen days at sea before finally arriving at Cam Ranh Bay. With backpacks and rifle in tow, the men had to crawl down ropes to get off the ship, descending into Higgins boats. John knew right away he was in a new world.

When on shore, the division was moved by truck to Pleiku in the central highlands of Vietnam. Pleiku was important strategically because it was the primary supply corridor extending westwards, and its central location between the north and the south, made it a primary center of defense. These factors were imperative to the U.S. Army for the establishment of a base.

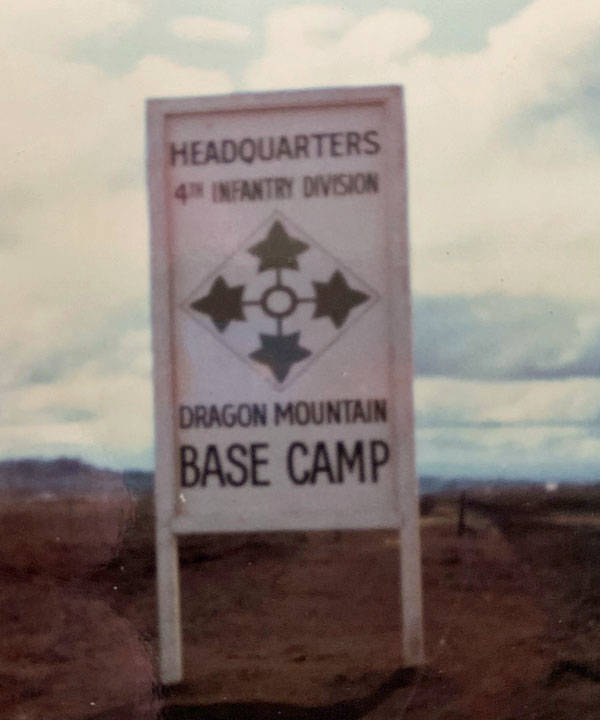

Being some of the first to arrive at Pleiku, John and his fellow engineers first put up tents and established a base camp at “Dragon Mountain.” Because of the heavy rains, they built platforms on stilts to keep their living spaces from flooding. The rain and flooding was so bad at times that even tanks were getting stuck in the mud. Life at the base camp was tough – taking a bath in a water truck shared by a hundred men, eating bad food, and braving the elements; but going on their weekly missions was even more harrowing.

When John received orders, a squad of engineers along with some infantry soldiers would board helicopters, and fly to who knows where for weeks at a time. All of the sudden the helicopters would stop, but not land. The soldiers were to jump out onto a field not knowing where they were or what they may encounter; but most importantly, would try to avoid “punji sticks.” These were a type of booby trap stake made out of wood or bamboo, that were sharpened and heated. They were so dangerous and did so much damage, that they were banned for use as weapons after the war. John saw his share of men encountering punji stick traps which has left lasting indelible images. Once on land, the engineers would clear trees and create landing zones for cargo planes. They would also clear roads of land mines mostly using a bayonet. John tells the story of how a young, 18-year old soldier who just arrived, was fatally wounded trying to defuse one near him. Every day they put their lives on the line.

What made the job even worse, was finding out about the massive underground system of tunnels the Viet Cong employed. These extensive tunnel complexes included ammunition and food depots, hospitals, training areas, storage facilities, headquarters, and barracks. It would allow the VC to live hidden underground for months at a time. The tunnels provided safety from bombing runs and gave the VC a strategic vantage point for attacks on U.S. troops passing overhead, and then slip back into their tunnels to seemingly vanish.

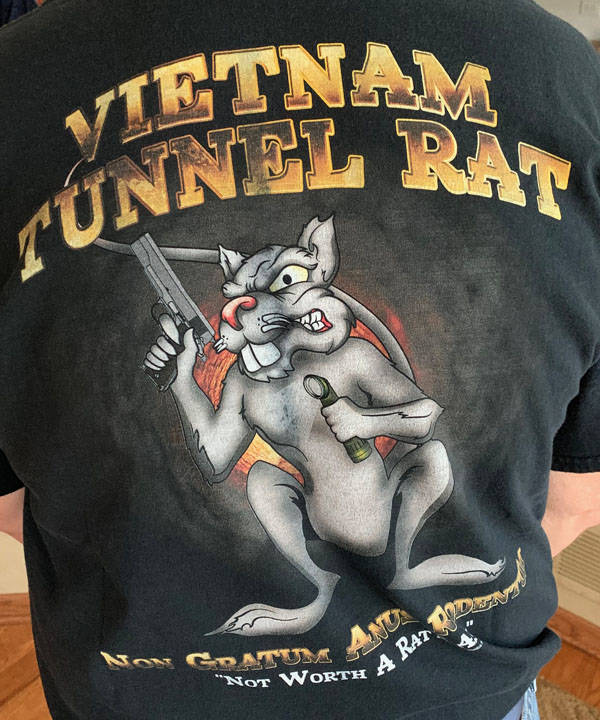

The only way these tunnels could be destroyed was to go into them and use explosives. Someone had to be the first to go into these small, tight entrances, and those soldiers who volunteered, became immortalized as “Tunnel Rats.” Because you had to be courageous, smart, and incredibly lucky to escape a tunnel without dying, their motto was known to all as “Non gratum anus rodentum” or “not worth a rat’s ass.”

Armed with only a flashlight and .45, John volunteered as a “Tunnel Rat.” One can only imagine the courage it took to enter one of these dangerous tunnels. You never knew what you would encounter even to the point of hand to hand combat with a Viet Cong soldier. The danger did not end there, for many of the tunnels had booby traps, poisonous snakes or insects and dangerous water or gases. The tunnels could also be incredibly hot and humid, cramped, and sometimes very small. Even exiting a tunnel was dangerous if you emerged elsewhere. There were many times when John thought he would never get back home to Chicago.

During his time in Vietnam, John saw his share of atrocities delivered by the Viet Cong. But he also met some great Vietnamese people. While guarding a certain village from the Viet Cong, he developed a friendship with the village chief. The chief made John a handmade carved peace pipe and friendship bracelet that John still has today. It gave him some sense of solace in an otherwise nightmare existence.

Then in January of 1967, while heading back to base camp after clearing another landing zone, John and the squad came under heavy mortar attack from the Viet Cong. He was hit with shrapnel in the head and legs. John was sent to Japan for surgery, and after a few weeks, was back in the U.S. at Hines VA Hospital where he received his honorable discharge. For his wounds received in action, John was awarded a Purple Heart.

John’s tour of duty left an indelible mark on him. He struggled for a while trying to get the horrors of war out of his mind. Thankfully meeting his wife Sylvia, and getting an opportunity to work at Commonwealth Edison helped ease the mental anguish and the pain. John and Sylvia have been married for almost 49 years now; he worked at ComEd for over 30 years.

Today, John talks fondly of his three children, Scott, Paul, and Kristen, and his grandchildren. He volunteers his time to his church, the Knights of Columbus, and the VFW Post. John is extremely proud to be part of the Honor Guard for military burials at the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery in Elwood, Illinois. John will be one of 30+ Honor Guard buddies sharing the October, 2019 Honor Flight day of honor to D.C.

For his time in the Army, John was awarded the Vietnam Campaign Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, National Defense Service Medal, and a Purple Heart. What he proudly wears today is a black Vietnam “Tunnel Rat” tee shirt which is really bad-ass, and something he has bravely earned.