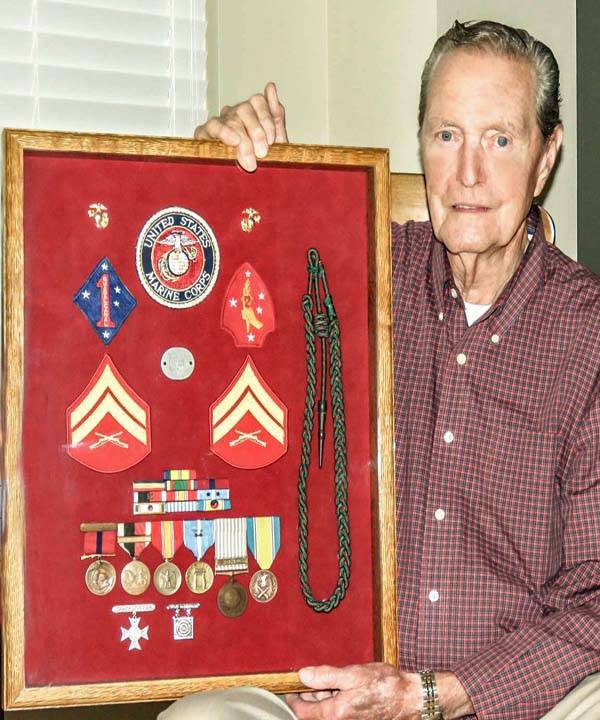

U.S. Marine Corps Korean War Vernon Hills, IL Flight date: 08/08/18

By Carla Khan, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

If John C. Muno ever had a nickname it would have been “Volunteer from A (as in A-Bomb observer) to Z (as in Korean War Zone warrior),” with many volunteer roles in between.

John was raised along with his two sisters and one brother in Rogers Park on Chicago’s North Side. He attended Armstrong Elementary followed by a parochial high school which he didn’t finish. Instead, he got a job with ComEd because he wanted to help his parents out financially.

In the summer of 1950, he decided to enlist because he had always secretly wished to become a U.S. Marine. So, one evening in September he boarded a troop-train headed to Boot Camp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, SC. On the train he met Ron, a fellow recruit with whom he’d become lifelong friends. Boot Camp was tough, but through total discipline such as no talking—not even during meals—and no relaxing for three months, these young men were shaped into tough Marines. They proudly graduated and then were sent on a 10-day furlough after which John had to report at Camp Lejeune, NC. He joined his Company and learned the use and tactics of light machine guns. Early in March 1951, John boarded the USS Randall (APA-224) headed for the Mediterranean to join the 6th Fleet, 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine, 2nd Marine Division. For four months they cruised the “Med.” As there was not much to do aboard the ship, John volunteered for whatever he could get his hands on, from manning the ice-cream machine to doing laundry. In July it was back across the Atlantic to North Carolina. This was followed by a stint in the Caribbean where they practiced landings and bombardings, much to the distress of the island population. The Marines were very good and thorough in what they set out to conquer, even when only practicing.

John then returned to the States and took a 10-day leave in Chicago. After all the heat and humidity, he actually hoped it would be cold in the Windy City. It was, and to make things even better he met a wonderful girl, Mary, with whom he continued a serious correspondence. He returned to Camp Lejeune hoping to be sent to Korea, but only those Marines with more experience were selected. Since camp life was “rather tedious,” John volunteered to participate in Operation Tumbler-Snapper at the Nevada Proving Grounds, where he witnessed “test shot DOG.” On May 1, 1952, an atomic bomb was dropped from an airplane and detonated. John and about 3,000 members of the military were told to “sit in trenches, with their backs towards the blast and to cover their eyes with their hands during the blast.” They were only four miles from Ground Zero, but no radiation protection was issued. John said that during the explosion he could see the bones in his hands “as in an x-ray.” This participation earned him the title of Atomic Veteran. On the train back to Camp Lejeune, his buddy Ron asked why he had such severe burns on his neck. Years later, he developed skin cancer but his doctors didn’t pursue the possibility of a link.

Next, John volunteered for a position as a small-arms instructor at Marine Corps Base Quantico, VA. He taught platoon leaders who had just completed ROTC training and referred to them as “the finest, ever.” Next, John returned to Camp Lejeune, where he earned his GED, and then on to Camp Pendleton, CA, for advanced infantry training. This included cold weather training to prepare the Marines for their deployment to Korea.

They left by ship and landed at Incheon in February 1953. John was assigned to George Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division and moved on to the 38th Parallel. John hoped to meet up there with his old buddy, but Ron had just been seriously injured and consequently evacuated. John and the other Marines manned machine guns stationed in hilltop outposts along the 155 mile-long trench. They were the Main Line of Resistance based on forward slopes.

Life was very hard in a frightening environment. The area was completely barren and had been stripped of all vegetation. There were just the trenches and two lines of barbed wire fences. The only living things were “rats the size of cats.” The Chinese set up enormous loudspeakers in an attempt to drown out all other sounds by playing American love songs followed by a message that sneered “and what do you think your wives and girlfriends are doing during your absence?” The messages alternated with offers of “wonderful things to anyone who would defect.” The Marines enthusiastically tossed their empty cans over the barbed wire fence to the enemy’s side. Shower tents were available only once in two weeks. In order to always be prepared for action, the Marines had to hold on to all their gear.

Listening posts were set up nightly, and at least monthly there were raids on the enemy, but the Chinese retaliated. While he was on observation duty in front of Outpost Vegas, he and his fellow Marines got involved in heavy fighting and suffered major losses.

On July 27, 1953, at 10 p.m., the Armistice was announced. John saw the incredible sight of huge numbers of Chinese soldiers came out with “gifts” concealing bribes. Time had come for John to return home, but he was briefly delayed for four days so POWs could be exchanged. The POWs were kept in isolation until they were debriefed and their health checked. After another ocean crossing, John arrived at the U.S. Naval Station Treasure Island, CA. He got cleaned up and hopped on a train to Chicago for a 10-day leave.

He used his time well and got engaged to the love of his life, Mary, to whom he would be married for the next 64 years. After his honorable discharge, John resumed his job with ComEd where he worked for the remainder of his long career. John and Mary continue their life and are enjoying their three children, 9 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. He also keeps in touch with his dear friend, Ron. John looks back with gratitude on his time as an active Marine where he learned about the values of pride and brotherhood.

Welcome Home, John! Thank you for your service and enjoy your well-deserved Honor Flight.