Air Force Vietnam War Flight date: 05/15/24

By Joe Kolina, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Suddenly, the still, black night exploded.

Air Force Sgt. Greg Dittemore heard a big boom, as a flash that looked like lightning crackled across the sky. His huge AC-119-K gunship shuddered as an anti-aircraft shell ripped into its nose. The lights went out. Everything went out. No instruments. No radar. No communications.

“POW!“ he remembers.

We’re sitting at the dining room table of his neat home on a quiet, tidy street in suburban Niles, Illinois, more than 50 years and 8,000 miles from Vietnam.

“I thought we were going to go down.”

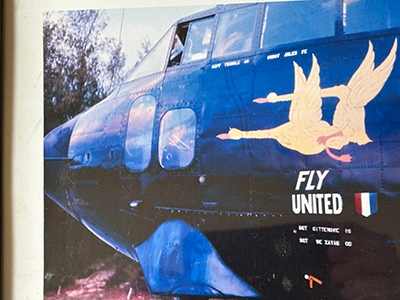

Luckily, it was the only shell from a fierce enemy barrage that hit its target. Somehow, the plane that the crew had nicknamed “Fly United” limped back home to Phan Rang Air Force Base, 200 miles north of what was then Saigon.

Greg says he knows his miraculous escape from death was a fluke, just chance. In fact, you could say his entire Air Force service, from 1968 to 1972, was a result of chance.

Greg grew up in Chicago in a part of what’s now known as the Little Italy neighborhood. He and his father didn’t always get along. Sometimes their battles were brutal. When he was 17 they had a particularly nasty fight.

“He said, ‘I hope you go to Vietnam and get killed,’” Greg says. “So the next day I went downtown and enlisted.”

Ironically, that spur-of-the-moment decision made in hurt, anger and defiance led years later to Greg’s unexpected reconciliation with his father. This is the story of what happened.

Greg completed basic training at Amarillo Air Force Base, then pursued mechanic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. But his eventual assignment to Scott Air Force Base near Belleville, Illinois, was a disappointment.

“I wanted to work on jets but didn’t quite qualify for them,” he says. “I still wanted to work on engines. But when I got there the only openings at Scott were on the interior. I wasn’t crazy about that.”

Then he heard about Operation Palace Dragon. His duty—and his life— were about to change dramatically in ways he could never have foreseen. It was late 1969 and AC-119-K Stinger gunships were going into service in Vietnam.

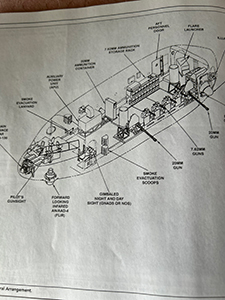

“They had a lot of firepower,” he says.

Crews used the two 20m Falcon cannons and four miniguns for precision attacks on transport trucks along the Ho Chi Minh trail, as well as to support ground troops and defend airbases.

Greg volunteered for duty and was trained as an illuminator operator at Lockbourne Air Force Base in southern Ohio. IOs provided the lighting for night missions. That included controlling the white and infrared searchlights at the back of the aircraft, launching flares, and working with gunners to identify and fire on the illuminated targets. Sometimes they were given specific missions. Sometimes they were ordered to just patrol and see what happened. Always, it was controlled chaos in mid-air.

“When all the guns were going, God, the fumes and the smoke. The decibels were ear-shattering. We had special noise-suppression helmets with microphones. But there were times we still couldn’t hear the pilots,” he remembers.

“And then walking through the plane. All that spent ammo and no place to catch it, so it’s just falling on the floor, you couldn’t walk hardly,” he adds. “And you’re hanging out the back door by a strap looking for ground fire.”

Chance did not favor everyone. Greg still remembers one who didn’t make it.

“He wound up drowning getting tied up in a line during a bail-out,” he says.

There was no such thing as an average flight. Greg recalls the mission where his crew was ordered to take out an elephant, of all things. The Viet Cong was inventive with ways to move material down the Ho Chi Minh trail.

“We were looking for a caravan of trucks when we saw elephants,” he says. “There were reports they were carrying ammo, so the pilot made some calls and they told us to go ahead and hit one, so we hit it. And sure enough, the elephant was loaded down with ammo,” he says, shaking his head.

Danger was ever-present, even at the base during down times.

“One night we were all in our hooches when all of a sudden a rocket blew out half of the wall a couple of doors down from me. Fortunately nobody was in that room, nobody was killed,” he says.

But Viet Cong soldiers had infiltrated nearby Phan Rang City and remained a constant, unseen threat.

“We always knew that anything could happen, anytime,” he says.

So, how did crews try to ease the unrelenting stress of life-threatening missions that came every two or three days?

“A lot of partying,” Greg answers with a laugh. His group was lucky enough to have amenities like air-conditioning, a makeshift bar, and an NCO club up the hill behind their quarters. And they shared space with a group of Australian fliers.

“They knew how to throw a party,” he says.

Greg spent a year in Vietnam as an illuminator operator before returning as an instructor to train other crews at Lockbourne Air Base, and later at Eglin Air Force base in the Florida panhandle.

He left the Air Force after four years in 1972. A difficult problem with migraine headaches he had developed during aerial combat eased with his return home and treatment. But Greg also experienced the scorn and criticism many Vietnam vets encountered back home.

“I was at O’Hare once, still in my uniform, and the first cab driver refused to take me home because I was in Vietnam,” he says.

There was an unexpected and emotional exception. Greg’s dad learned about his service, the sacrifices he made and the danger he put himself in for his country. He learned that his son was the rare IO who had completed jump school, and was so good at his job that he had reached the highest rank for a non-commissioned officer in the Air Force.

“He told me he was proud of me,” Greg says of the man who had once wished in the heat of an argument for his son to die in Vietnam. “It was a big turnaround, 360-degrees. My father and I became good friends.”

Greg says he thinks most young men would benefit from at least one tour in the service.

“I found out what life was all about,” he explains. “No more mother’s apron strings. Rules and regulations to follow. It changed me from my cocky punkiness. It built character. I picked up a lot along the way.”

Time has healed the wounds. Greg says his reception in public has changed dramatically.

“I wear my Vietnam hat everywhere,” he says. “And I can’t tell you how many times people now stop and thank me for my service. A big difference. It’s unbelievable.”

Greg goes to reunions of AC-119 crews and enjoys meeting and reminiscing with fellow Vietnam vets.

“It just reminds you of what you went through, what you did, and how proud you were to do it,” he says.

Greg can’t wait to go on his Honor Flight. It will be his first time visiting the monuments in Washington. His lovely wife, children, 12 grandchildren and 5 great-grandchildren are all so proud of him and so happy about his selection.

When I ask Greg what he is most interested in seeing in Washington he barely pauses before answering.

“I want to see everything, I want to talk to everyone” he replies.” It’s nice to know your story is out there and people haven’t forgotten you. It makes a difference.”

Here’s hoping the trip is everything Greg dreams it will be.

He deserves it. He earned it.