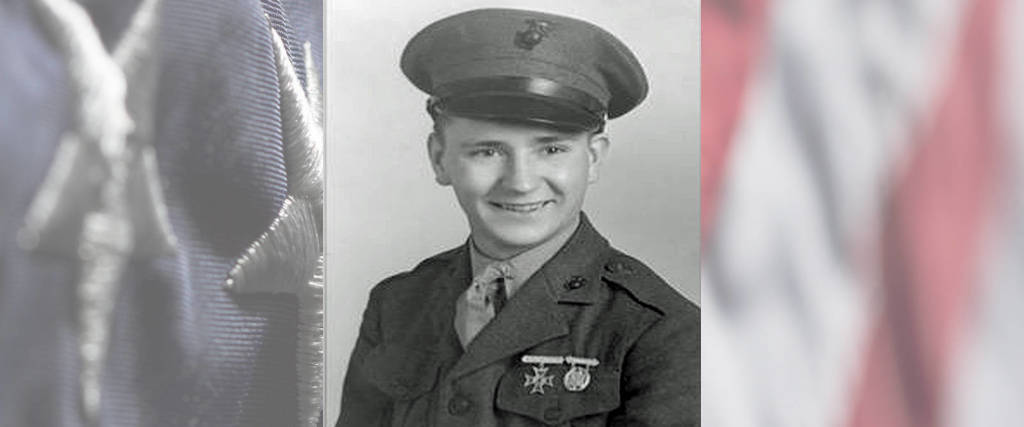

U.S. Marine Corps World War II Park Ridge, IL Flight date: October, 2019

By Paul Mally, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

“It was October 1945 and I was listening to the 6th game of the 1945 Cubs-Tigers World Series over my high powered jeep radio in China.”

PFC Gene Bednarz ended up halfway around the world from his Chicago home listening to a ball game. His journey to China took him and his Marine Corps buddies across the Pacific, stopping to fight in some of the most savage battles of World War II.

Gene grew up near Ashland Ave. in Chicago and went to Holy Trinity Church. He became eligible for the draft in 1943 when he turned 18. At the time, he was an engineering student in his second year of college at the Illinois Institute of Technology and was given an automatic student deferment. Engineers were in great demand and the deferment was welcome news to his Polish-born parents who agonized about the war ever since Poland was invaded by Germany in 1939. They were proud to have their eldest son attending college, but fearful that he would be called into service. The college deferment calmed their fears.

As a live-at-home student, Gene found it difficult to concentrate on his studies while several former high school classmates were being inducted into the services. When he was called before the draft board for a six-month review, he refused the deferment, and enlisted in the Marines. “I had seen the film Guadalcanal Diary about the 1st Marine Division and I guess I wanted to be a hero.” Gene’s parents were greatly disappointed. “I’ll never forget seeing my mother for the last time that warm, sunny August morning, waving a tearful goodbye as I turned a corner on my way to the USMC Recruit Depot in San Diego. That image has stayed with me ever since.”

After three months in Boot Camp and three weeks on the rifle range, Gene was sent to the radio school in San Diego. The fine California weather, classes during the day, family style meals, no marching or military exercises of any kind, overnight passes to visit San Diego during the week, and 3-day passes to hitchhike to Los Angeles and Hollywood over the weekends made for great duty!

And then in February of 1944, three weeks short of graduation, tragedy struck. Gene received a telephone call from Chicago that his mother was gravely ill and that he should come home as soon as possible. He immediately applied for leave and was given a two-week pass, plus a reserved seat on a flight to Chicago for which he had no money. His buddies in the squad room took up a collection to pay for the ticket. Before he boarded the plane that evening, a Red Cross nurse informed him of the death of his mother. “What? My mother was dead? No that couldn’t be! A mistake! She was 44, in the prime of life! No, it’s not possible. I was told later her death was caused by a post-op accident. No one was at fault. There was no one to blame, except maybe me.”

The following months were a blur. Returning to San Diego, Gene was placed in another radio class to complete the course. After graduation, he was promoted to NCO status, but remained a Private and was assigned to a combat infantry battalion based at Camp Pendleton. His radioman classification was apparently either ignored or not pertinent; he spent several months in training as an infantry rifleman which would come in handy. There were 20-mile hikes and overnight bivouacs in the hills, hand grenade practices, digging and sleeping in foxholes, fire-team deployments, etc.

In May ’44, the battalion was deemed ready for combat and boarded an old French luxury liner that had been inadequately converted as a troop transport. The conditions were crowded with too many troops and too few facilities. (There can be as many as 1,000 men in a battalion.) Gene was assigned the lowest of a 5-tiered hammock, right over the propeller shaft housing. Beside the constant grinding noise and the rise and fall of the aft of the ship, there was a great deal of seasickness below decks. To avoid all of that, he spent almost the entire 30-day trip amid ship above deck. The weather was warm and clear, and the Pacific relatively calm, but sleeping on a steel deck was no fun. To help pass the time “I took advantage of the pocket-book library on board and that was the beginning of a life-long habit and love of reading.”

Finally arriving at a South Pacific staging area, Gene and another Marine were called out by name and told to bring along their sea bags with no explanation why. They boarded another ship that took them to a seemingly deserted beach on a small island, and were told to wait there. It was raining and there was no visible activity. A jeep came and the driver took the men to their posts. “I was assigned to the Radio Section of the Communications Platoon of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Regiment of the 1st Marine Division! What irony! If I had had the opportunity to pick any unit that I would have wanted to join, it would have been the fabled 1st Marine Division! And as a radioman after all! I was in awe! I had been selected to join the heroes of Guadalcanal, a name and event most Americans had heard and read about!”

The original platoon members were largely indifferent towards the new replacements. However, as the days wore on the atmosphere gradually changed as tensions eased and the men relaxed. Conversations began to flow. The 1st Division had just returned from a tough campaign on Cape Gloucester in New Britain where the jungle was wet, steaming and unforgiving. Some members were “Old Salts,” professionals who had joined the Marine Corps during the depression years before Pearl Harbor. The island was a coconut plantation called Pavuvu. It was the Division’s rest camp that all the men hated and with good reason. It was rat and crab infested, and much too small for the Division’s personnel. “The TV mini series The Pacific showed almost exactly how things were.”

After practicing beach landings and simulated jungle fighting on nearby Guadalcanal, the Division set sail for the Palau Islands. On the morning of September 15, 1944, 9,000 Marines of the 1st, 5th and 7th Regiments invaded Peleliu. Gene was in the second wave. “I climbed down the cargo net into a bobbing Higgins boat, then before landing, we had to transfer to an LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked). I had on all my gear, ammo, M1 carbine and my 40 pound SCR 300 radio. As I tried to make the transfer, I had one leg on each boat and then they started to drift apart! Luckily the guys pulled me in or I would have gone right to the bottom!”

What was imagined to be a two- or three-day campaign turned out to be prolonged, unimaginable carnage instead. The key objective on the island was the airfield; Gene participated in warding off a Japanese counterattack and then seizing it from the enemy. In all, 1,252 had been killed and 5,274 were wounded, for a total of 6,526 Marine casualties. “Of the original 12 men (mostly 19 and 20-year-old boys) in the Radio Section, three were evacuated with grievous wounds, while four with lesser injuries (myself included), and five who had been incredibly lucky to be unharmed, returned to Pavuvu.”

“Fresh replacements were waiting for us. We ignored them and didn’t feel like we had anything to say to them. We needed time to return to normal, if we ever would. Eventually we did, sort of. The reticence dissipated and we became comrades in arms as we prepared for the next island assault.” It came six months later on Easter Sunday morning, April 1st 1945, (April Fool’s Day in the U.S.), when the 1st Marine Division, along with the 6th Marine Division and several Army Divisions invaded Okinawa. The landings were virtually unopposed. The Marines quickly secured the northern half of the island where heavy resistance had been expected, but did not occur. The Army on the other hand ran into a wall of resistance they could not overcome. After several weeks with no progress, there was only one solution – send in the Marines. “ My fellow veterans of Peleliu and Okinawa have often joked that compared to Peleliu, Okinawa was like a leisurely stroll in a park. That was true while we were in the northern half of the island, while the southern half was another story. The combat conditions on Okinawa were not in any way close to the mayhem and chaos of Peleliu, but Okinawa was no picnic.” While on Okinawa, Gene served along with some of the Navajo “Code Talkers.” One of them was named Billy Cleveland. “They communicated in their Native American language between Battalion to Regimental HQ. The Japs never figured out what they were saying!”

After Okinawa was secured around the middle of June, the Division began intensive preparations for the attack on the main Japanese islands. With the suicidal tactics the Japanese employed on Peleliu and Okinawa, the Marines expected to encounter even more desperate suicidal Japanese defenses when they invaded the mainland. The atom bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August resolved those concerns. “I don’t believe anyone who ever fought against the Japanese ever questioned the morality of using the atom bombs. It would have been immoral to have the bombs and not use them, to sanction instead the slaughter of untold thousands of marines and soldiers who would have invaded the Japanese mainland. Japanese civilians were killed? Weren’t the soldiers, sailors and marines who were killed not also civilians temporarily in military units?”

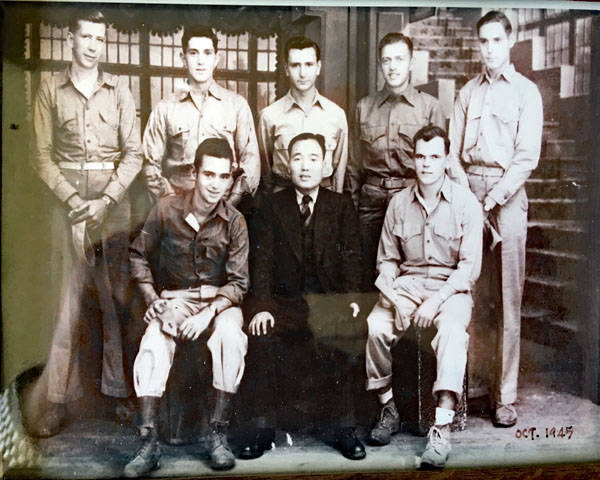

Instead of an invasion of Japan, the war ended. Gene and his unit were sent to Tientsin in northern China for occupation duty. There were still thousands of Japanese troops there who had just surrendered, but the main objective was to protect the railroad lines from the Red Chinese Communist troops under Mao Zedong. While there, Gene came down with a case of amoebic dysentery and ended up in the hospital. After he recovered, because he had enough “points” he was shipped back home. “When I got home there was no hoopla. Everybody in the neighborhood had been in service. We just got on with our lives.”

The close friendships and bonds developed during the war did not end in civilian life. “We stayed in touch, visited many times over the years and got to know each other’s families. The wives also bonded. We also got together at many of the 1st Marine Division reunions, usually held in a major city on or near August 7th, the anniversary of the Guadalcanal landings.”

“I have never had any nightmares, nor lost any sleep because of the savagery of Peleliu and Okinawa, but I have often thought of my mother and prayed for her forgiveness. I’m sure she not only forgave, but also watched over me and kept me safe, not only on Peleliu and Okinawa, but also during all the intervening years.”

Gene returned to IIT under the GI Bill in the fall of ’46 and graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering, to the delight of his father. He married his wife Gloria and had a long, happy marriage together before she passed away just this summer. “ I have three grown children and 10 grandchildren. They all live within a 30-mile radius and visit often – OR ELSE!”