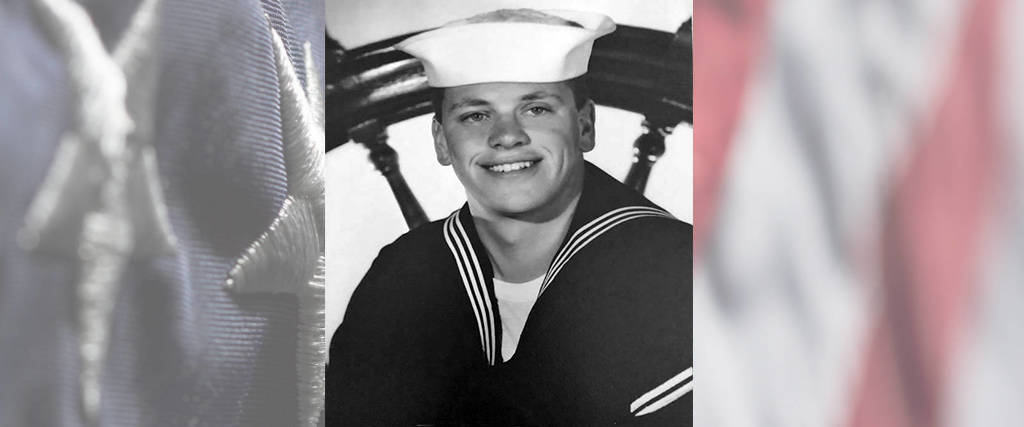

Coast Guard Vietnam War Des Plaines, IL Flight date: August, 2019

By Wendy L. Ellis, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Three times Gary Nelson has traveled to Washington D.C. with Honor Flight Chicago, each time accompanying a World War II veteran on this journey of thanks. The next HFC flight on August 7th, 2019, will be Nelson’s fourth, but this time it will be different. This time, he’s the veteran being thanked.

Unlike many of his fellow veterans on this trip, Nelson served his country as a Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class in the U.S. Coast Guard from 1963 to 1967. He grew up in Wisconsin on Washington Island, one of a line of small islands in Lake Michigan just north of Door County. Nelson was used to being surrounded by water. His parents owned a restaurant on the island, a popular tourist destination in the summer months. He and his two older brothers couldn’t escape the family business; they had to bus tables, do dishes and help with general cleanup, before heading to the beach every afternoon when chores were done. Winter months saw a lot fewer tourists and a lot more ice. The winds howled around Washington Island and the daily ferries dropped from hourly to two a day.

“People always ask me how it was growing up there,” says Nelson. “I don’t think we even realized we were growing up on an island.” When Nelson graduated from high school in 1963, he was one of a class of six graduates – one girl and five boys. He wasn’t really thinking about college. Instead he followed one of his older brothers into the U.S. Coast Guard.

“There was a coast guard station on the next island, Plum Island, and several men on our island were either in it or retired from there. My brother had joined the year before, so I did the same.” His brother had been assigned to the icebreaker USS Mackinac (AVP-13) and spent most of his Coast Guard years on Northern Lake Michigan. Not so for the younger Nelson. After Basic Training, and a short stint at a Coast Guard station in Kenosha, he was sent to Gunner’s school for 9 weeks in Connecticut, and then posted to Alameda, California.

There he was assigned to the Coast Guard Search & Rescue ship, Ganey, a 327-footer. Their assignment was to patrol the Gulf of Alaska, watching for Russian fishing boats and making sure they didn’t cross into U.S. territorial waters. “They never did,” says Nelson. “But we could see them every day off in the distance.” At one point, the Ganey was sent to the middle of the Pacific Ocean between California and Hawaii to act as a point of reference. “We sat there for a month as a beacon for other ships and aircraft, so they knew where they were in a dark ocean.”

There were similar duties on his next ship, the Ewing, which was patrolling the waters off Carmel, California, maintaining buoys and lighthouses. “Most of our search and rescue was going out and getting Mexican fishermen who would carry just enough fuel on board to get to their nets, but would call us to tow them back,” says Nelson.

Seattle, Washington, was Gary’s next assignment and an Icebreaker named USCGC Staten Island – destination Antarctica. The Coast Guard called it Operation Deep Freeze. “We were supposed to go to Tasmania, but the evaporators on the ship that turn saltwater into freshwater, broke, so we ended up in Pearl Harbor for a month getting the evaporators repaired,” says Nelson. “Never got to Tasmania. We left Hawaii and crossed the equator on Thanksgiving of 1966 heading to New Zealand.” Not all was smooth sailing. The ship encountered the infamous Roaring 40s and Furious 50s, between the 40th and 50th parallels. The intense westerly winds caused the bow of the ship to dip low into the water and come back up so fast there was green water spraying onto the bridge of the ship. Even experienced seamen were getting seasick. They made it through and on Christmas Day of 1966 they spotted their first icebergs. “All I could think about was the power of nature,” says Nelson. The crew spent the next couple months breaking up the ice around McMurdo Station clearing the path for ships bringing supplies to the people who would winter-over on the southernmost continent. Nelson said he never had occasion to use his gunnery skills while on duty. “I had gone to demolition school, too, so my job on the ship was to go out and blow up the ice if our ship got stuck in it. Fortunately, we never did.”

Twice they would make the 3-day trip back to New Zealand, again passing through the Roaring 40s, to pick up supplies and scientists destined for Antarctica. Their constant companions on the ice were herds of penguins and seals basking in the sun. For Antarctica, Christmas time is in the middle of summer and temperatures were in the 30s.

Despite the previous repairs, the ship was still having water filtration problems. Before they could leave Antarctica, the Staten Island had to cozy up to another icebreaker on duty nearby to get water. Unfortunately, they cozied up too close and punched a hole in the other ship—time to leave!

Two months after returning to Seattle, Nelson mustered out. He started a 41-year career with Illinois Bell, staying on as an installer and repair technician through all Ma Bell’s iterations. One positive thing came of his career early on. He was called to Resurrection Hospital to repair the phone of one of its nurses. “Since I’d fixed her phone I knew her phone number,” says Nelson. “So I called her up and asked her out.” She said YES and they have been married since 1980. They have one daughter and a grandson.

Nelson is very much looking forward to his next trip with Honor Flight Chicago. The time he has spent with the WWII vets he accompanied means a lot to him. “They may not have talked much before but on this trip they opened up, veteran to veteran. They had a lot of stories to tell. The things they’ve gone through. War is hell. I’m excited about going even though I know what’s going to happen. It’s a fantastic group.”