Army Vietnam War Downers Grove, IL Flight date: 08/28/24

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Donald Clarke was born near Boston in 1948 and grew up next to the Revere Beach amusement park and boardwalk. His family has a strong history of fighting for the United States, including his grandfather who was a World War I veteran and his father and uncles who fought in World War II. He was a good athlete in high school and played football, baseball, and basketball. After graduating high school in 1966, he did several odd jobs, and then in 1968 he enlisted in the Army, partly because he didn’t want to hang around with some of the neighborhood kids who he knew were going to get in trouble, but mostly because he wanted to serve his country.

Boot camp for Donald began in January 1968 at Fort Knox, Kentucky. He describes it as “tolerable” and while the instructors were often in the faces of the recruits, they weren’t as physically abusive as what his friends in the Marines experienced. He was at the top of his class in shooting and qualified as a sharpshooter. He was assigned to be an artilleryman, so after boot camp he went to Fort Sill, Oklahoma for eight weeks of artillery school. The training at Fort Sill was more like school than like boot camp, and he only spent about twenty percent of his time actually at the range firing his howitzer. He did enjoy the food more, though, and says it was an upgrade compared to boot camp. He volunteered to go to Vietnam, so after some additional training at Fort Bragg, he flew to Vietnam, arriving in August 1968.

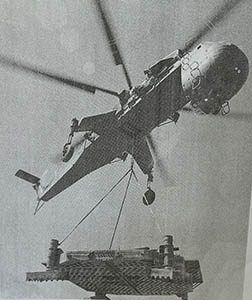

Donald was an artillery gunner assigned to the 34th Field Artillery Battalion of the Ninth Infantry Division, and he spent his entire time in Vietnam in the Mekong Delta. Since the swampy terrain of the delta was not well-suited for 105mm howitzers, the army used “paddy platforms.” Each platform could support one howitzer and could be airlifted to wherever it was needed. When it was time to move to a new location, a CH-54 crane helicopter would arrive and pick up the platform. Donald says it was “like a hurricane” when the huge helicopters came in for a pick-up, and the soldiers quickly learned not to stand next to any loose items that could be blown into their faces and bodies. Sometimes the legs of the platform would be stuck in the mud, in which case explosive devices would be used to get the legs unstuck. The helicopter would then carry the platform to the next location, and Donald’s unit would follow in other helicopters. Through repeated practice, they could establish a new base and surround it with barbed wire very quickly.

Donald’s unit was in the field almost continuously during his four months in Vietnam, moving from one location to another and usually only staying in one spot for a couple of days. Once they arrived at a new location, they would wait for the calls to come in for artillery support from the infantry units. While they waited, they cleaned the guns and checked shells, powder, fuses, and projectiles. They were on call 24/7 and often didn’t have much warning as to when they’d be needed, so they had to be constantly vigilant and prepared to fire at a moment’s notice. When they received the coordinates of their target, they’d fire one test round. A spotter would radio to let them know if it was accurate or if it needed adjustment, and once they received the OK then all the guns would fire. Fuses were usually set so the shell would explode a few meters above the ground to maximize the kill radius.

Because of the terrain of the Mekong Delta and the guerrilla nature of the Vietnam War, Donald’s unit was always in danger. The massive and loud resources required to establish a new firing base alerted local enemies of their position. Nearly every day, Donald’s unit had some sort of interaction with enemy forces, either through mortar attacks or soldiers trying to infiltrate through the barbed wire. They lost men regularly and often didn’t have enough soldiers to man the guns in their unit. Standing on a platform in the middle of a rice paddy, Donald says they were “sitting ducks”. Their only protection was the barbed wire plus a few men scattered at different points around the perimeter. Occasionally these men would fall asleep while on watch, putting themselves and the entire unit at risk. When attacked, they’d sometimes call in air strikes, usually in the form of napalm from F-104s or minigun fire from AC-47 gunships. Donald recalls that he and his fellow soldiers would cheer when the aircraft hit their targets.

On the night of November 22, 1968, an enemy force infiltrated the perimeter of their base. Their section chief was seriously wounded, and while it wasn’t immediately clear how many enemy soldiers were involved, the entire unit was clearly in danger. Donald immediately took action and raced to the gun platform where he switched the gun’s usual high explosive rounds to “beehive” anti-personnel rounds. Rather than the usual artillery rounds that are fired using indirect fire, beehive rounds are fired directly at enemy troops and explode into hundreds of small darts. Since the enemy was so close, Donald set the timer on the shells so they’d explode almost immediately after leaving the gun. After firing several of these beehive rounds, he switched to a .50 caliber machine gun and sprayed the area where the enemy was attacking. He didn’t stop shooting until his lieutenant dragged him off the platform and told him it was over. For his actions that night, Donald was awarded a Bronze Star with a V for Valor. His commendation states that “Private Clarke’s gun provided the backbone of the defense of the fire support base as it continued to fire on the enemy forcing them to withdraw.” It further states that his “personal bravery and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service.”

Just a few weeks later, on December 11, evening was settling in when Donald’s unit was hit by a mortar attack. A shell landed directly in front of him, causing massive damage to his face and chest. He woke up in an Army hospital with bandages all over his face, and after several days, was flown to a hospital in Tokyo. After a month there, he was sent back to the United States, where he spent nearly four months at a hospital near his home in Massachusetts. He was discharged from the hospital and from the Army in April 1969 and has been dealing with the health consequences of his service in Vietnam ever since. He lost sight in his right eye and still has shrapnel in his skull.

In 1970, Donald decided to go to college and enrolled at Tampa University in Florida. In the time since he left the military, he had let his hair grow out, and the first administrator who saw him said, “Looks like we got a hippy here.” He graduated after two years and then spent most of his career working for a telecommunications company. In 1984 he was transferred to the Chicago area and has lived there ever since. After taking early retirement from that firm he started and then sold his own business, and has also done some consulting work. Just a few weeks after starting college, Donald had met the woman who became his first wife. They were married in 1973 and had two children, but sadly, she died in 2003 after a long battle with cancer. He remarried the following year, and they’ve been together ever since. In retirement, he is an avid reader and enjoys watching his six grandchildren play sports, traveling with his family, and spending time with his three dogs.

While Donald doesn’t like to talk about his Vietnam experiences, he’s proud of his service to his country and feels that the United States was trying to do the right thing, but unfortunately failed. He never knew what his guns were firing at and didn’t want to know, but he did know that he was fighting for America and defending our flag. Despite his injuries, he says that Vietnam was “a good experience” and that he’d do it all over again. To emphasize the point, when the Gulf War started, he went to a recruiting station and volunteered, but had to admit that he had some physical limitations and he was therefore turned down.