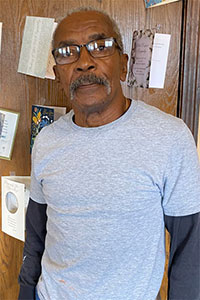

Army Vietnam War Maywood, IL Flight date: 10/19/22

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Clyde Hall, Jr. was born in Mississippi in 1948, one of seven children and the son of a World War II veteran. When he was seven his family moved to Chicago, but after his sophomore year of high school, Clyde moved back to Mississippi to help out his grandparents who still lived there. He graduated from high school in Mississippi and then came back to Chicago where he got a full-time job and also began studying bookkeeping at Triton College. Working full-time while attending college was difficult, and since he couldn’t afford to leave his job, he decided to lower his class load. In 1968, he dropped from 13 semester hours to 11, even though he knew that meant he was no longer considered a full-time student and therefore was ineligible for a draft deferment. Six weeks later, he came home, found his mother crying on the front porch, and discovered that he had been drafted.

He was inducted in February of 1969 and did Basic Training at Fort Polk, Louisiana, where he recalls that a lot of the young men, often fresh out of high school, had a really hard time. He then did advanced infantry training at Tigerland, a U.S. Army training camp, which was specifically designed for soldiers being sent to Vietnam. He volunteered for a leadership preparation course and then, partly in an effort to stay in the U.S. as long as possible, he requested to go to NCO school at Fort Benning, Georgia. After the three-month course, he stayed there for an additional three months in order to help train the next class. By the time he was done with all of this training, he had only eleven and a half months left in his enlistment. He had heard that they weren’t sending men overseas who had less than a year left, but this wasn’t true. After coming home for seventeen days, he left for Vietnam in early 1970.

Clyde says it never really hit him that he was going to Vietnam until they landed at Cam Ranh Bay and he saw rockets being fired in the distance. Their bus had heavy screens on the windows and sandbags on the floor in case they hit a mine. He was struck by how young everyone was, and at twenty years old, he was the second oldest soldier in his platoon. He was in the Americal Division, an infantry division of the Army. Their unit was quickly sent out to the field. He was based in Chu Lai, which is ninety miles south of Da Nang, specifically at LZ Bayonet and LZ Dottie.

Clyde was a squad leader, with a rank of E-5, or sergeant. At both LZs where he was based, their role was to go out on patrol every few days. Sometimes they patrolled their location by helicopter and other times by truck. Generally, an entire platoon would go out, and the squads within the platoon would stay in contact via radio. They’d look for munitions that hadn’t exploded, attach C4 to them and blow them up; they were constantly on the lookout for mines and booby traps. That area of Vietnam was a combination of jungle and tall, thick, wet grass. In addition to snakes and mosquitos, leeches were a constant concern. Whenever they returned to base, they would look for leeches and pour gasoline on them to make them let go. On average, they’d encounter the enemy and have firefights once every couple of weeks. When contact was made, the VC would sometimes “di di mau” or run away after a brief firefight, knowing that artillery or air support would probably be hitting them shortly.

Clyde’s squad also went on night ambushes. They’d always wait until dusk to go out so the enemy couldn’t see where they were going. They’d stay awake all night, with Clyde making sure nobody fell asleep, since that would risk the safety of the entire squad. Squad members would face in all directions to ensure that they were covered; these patrols were difficult because the VC always knew the area better than the Americans did. Of the fifty or so night ambushes that Clyde’s squad went on, they only made contact with the enemy twice.

Clyde earned the nickname “Squirrel” while he was in Vietnam because he couldn’t sit still and was always busy doing something. He did his best to make sure everyone in his squad was safe, even if that meant chewing out men who weren’t doing their job. They did what he asked because they knew it was for their own good. Because he treated the men with respect and did what he could to keep them safe, men always wanted to stay in his squad or move into his squad. He always told his men that if they did what he asked he wouldn’t let anything bad happen to them, but sometimes things occurred outside of his control that prevented him from keeping that promise.

One morning Clyde’s platoon was assigned to set up a night defensive position on top of a hill. One squad was on the hill while the other squads, including Clyde’s, were at the base. Clyde heard an explosion and realized that the squad on top of the hill had walked into a minefield. Two other mines exploded before the other squads were able to assist in the evacuation. As the first squad was evacuated, the relief squads hit four other mines. A man near Clyde stepped on a mine and the explosion threw Clyde ten feet in the air. He landed in a seated position with his legs underneath him. As he slowly regained his senses, he looked down, couldn’t see his legs below the knee, and thought they had been blown off. Blood dripped from his face onto his lap.

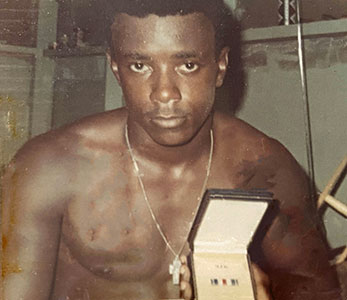

He had shrapnel in his face and abdomen and was numb from the concussion of the explosion. As the numbness wore off, he realized that he was sitting on his legs and also realized that the man who stepped on the mine was hurt much worse than Clyde. He crawled to him and saw that the only thing holding his foot to his leg was his sock. Clyde tied a tourniquet to his leg and waited for the medic to arrive. He then looked around and saw that the other men were frozen, afraid to move because of all the mines. They were crying, cussing, and praying, and the only place they felt safe was the ground they were standing on. He took control of the situation, cleared a landing zone for helicopters, had the wounded men medevaced out, and safely evacuated the other men from the area. Several men from his squad were injured and one was killed, the only member of his squad to be killed while Clyde was there. In total, three men were killed and 23 were injured. Clyde says it was the worst day of his life. Later, he received a Purple Heart and Silver Star for his actions that day. In December 1970, he got a 30-day early out and made it home in time for Christmas.

Clyde had gotten married right before his NCO training and has now been married for 53 years. He and his wife, Dorothy, have five children and four grandchildren. When he came home from Vietnam, he got a job at Duo-Fast in Franklin Park, which is where he had worked before the Army. He ended up doing an apprenticeship to become a tool and die man, which is what he did until retiring in 2009. But just like “Squirrel” from Vietnam days, Clyde has to stay busy. He now operates a handyman service and spends as much time as he can on his passion, bowling.

Thoughts of Vietnam come back to Clyde often, and sometimes the memories are so vivid that it’s like they happened last week. He had a great support network while he was in Vietnam, and he got mail nearly every day, which he says was the key to getting through it. He also had a strong support network when he returned, and he recognizes the issues with the men who didn’t. There are some things he can’t talk about and some movies he can’t watch, but overall he says he’s doing fairly well. He still has a fragment of shrapnel in his cheek from the day in the minefield, and while doctors have offered to remove it, he’s chosen to leave it there as a memory of his experiences.

Over the years, he lost touch with most of the men from his Army days, but recently a man from his NCO training program reached out to him and they talked to each other for the first time since 1969. He knows he was lucky to come home and recalls a time when he was talking to another man on the ledge next to a bunker. A 7-Up can was between the two men and as they talked, a sniper’s bullet hit the can. People used to tell him there was a bullet with his name on it, but he says the bullet that always concerned him the most was the one that said, “To Whom it May Concern.”

Thank you Clyde for your courageous service to your country. Enjoy your well-deserved day of honor with Honor Flight Chicago’s 106th flight.