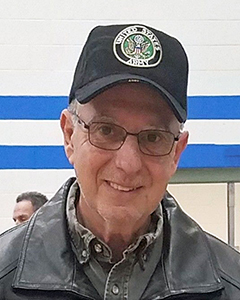

Army Vietnam War Flight date: 09/25/24

By Joe Kolina, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

It might surprise you to learn what Bob Shervino remembers first when people ask about serving as an infantryman in Vietnam.

“God was I hungry,” he says. It’s 55 years later, but the pained look on his face makes it seem like yesterday. “Sometimes I would force myself to go to sleep just to forget how hungry I really was.”

SPC/4 Shervino served in a mortar platoon as part of the Americal Division 198th Light Infantry Brigade. He carried a lot on his back when he went into the rugged Vietnamese countryside on patrol. The platoon split up the heavy mortar equipment. That meant up to 50 pounds for each man, and at least one mortar round. Then there was a rifle plus ammunition. And more.

“I didn’t like to carry a lot,” he remembers. So he didn’t pack much food. And what he did bring was mostly fruit. Pineapple was his favorite.

“I remember being hungry a lot,” he says. “And I remember my teeth hurting me, probably from not eating anything solid.”

Bob Shervino saw his share of combat in Vietnam. The citation for his Bronze Star testifies to the extreme danger he faced and the bravery of his response. What strikes me when we meet in his Tinley Park, Illlinois, home is his attitude about the Army, the war, and its aftermath.

Bob grew up in the West Englewood neighborhood in Chicago. He graduated from Bogan High School and spent two years in college. Then he made a big decision. He dropped out and waited for his draft notice.

“I felt like I had a military obligation,” he says. His father and uncles had served. “I felt it was something I should do.”

In January 1969 Bob had a college deferment. He was drafted in May. By October, he was fighting in Vietnam. His action took place outside of Chu Lai, a strategically important base of operations in central Vietnam, about 60 miles southeast of DaNang. Bob’s mortars provided support for rifle platoons. Patrols were perilous. It was hot and rainy. Enemy troops hid in the thick jungle.

“We would go out until somebody shot at us,” he says. “You never knew when, so you had to always be on your guard.”

Bob dealt with the life-threatening uncertainty by developing an attitude he called “no brains, no feeling.” Don’t think about it. Don’t talk about it.

“I just tried to stay aware, not overthink,” he explains. He told himself to just get on with it. “You were there. You were going to be there for a year. You just went about your business.”

Sometimes that was easier said than done. Take June 5, 1970. The night was pitch black. Soldiers on patrol were settled in camp. Suddenly, all hell broke loose. First, the rapid RAT-A-TAT-TAT of rifle rounds. Then, the ear-splitting BOOMS of explosions inching ever closer. And finally, the frenzied confusion of an all-out ground assault.

“We started shooting illumination rounds,” Bob says. “We had it lit up like daylight so the rifle platoons around us could see the enemy. Then we started firing high explosive rounds, too.”

The next few minutes are a blur. Bob downplays his role. Here’s how the official citation for his Bronze Star describes what he did that day.

“With complete disregard for his personal safety, he kept his gun crew supplied with ammunition, despite enemy rounds impacting within 15 meters of his position,” it says.

“Repeatedly exposing himself to enemy barrage, he carried urgently needed ordnance to the mortar pit, which enabled his comrades to provide uninterrupted support,” it says.

“Through his timely and courageous actions he contributed significantly to repelling a determined enemy assault and minimizing casualties.”

The citation ends: “His personal heroism, professional competence and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service.”

Sometimes Bob’s “no brains, no feeling” approach helped him deal with the utter absurdity of menacing situations that arose quickly and resolved just as fast. For instance, Bob says soldiers were instructed to burn their mail from home after they read it.

“If we were to get captured, they could use that against us,” he explains. “They’d know where you live, your girlfriend’s name. They would know everything.”

One day Bob strayed a bit from the perimeter of his base to burn his letters.

“I’m crouched down and I’m lighting my mail when the ground around me starts smoking,” he says. Snipers had suddenly opened fire on him.

“I hit the deck,” he adds. “I buried my head in the dirt and everybody starts firing.”

The fighting quickly grew so intense his captain called in a helicopter gunship for cover. In just minutes all the shooting stopped and everyone returned to what they’d been doing. It was as if nothing had happened.

On another occasion, Bob was in the field when he fell asleep.

“I woke up and there were shell casings all around me,” he says. It turns out there was incoming fire while he was asleep. The machine gunner next to him didn’t wake Bob up because the shooting was over before he knew it.

“Talk about how you get accustomed to things,” Bob says with a shake of his head. “I didn’t hear anything. I know this sounds silly. I just remember being so tired.”

There was, however, one instance where Bob’s ability to take things in stride failed him. It involved a popular, beloved chaplain, who never made it home.

“I remember meeting with him one time,” Bob says somberly. “We just got into a private conversation. I told him I was scared. And he said, you know, we’re all scared.”

Tears come down Bob’s face as he talks about the chaplain. He pauses, then looks away for a moment. He wipes away the tears with his hand. All this time later, he still mourns for the kind man who sat with him and helped him get through a difficult moment.

“It just bothered me,” he adds. “It just didn’t seem right, didn’t seem fair. He was providing comfort for everybody else. He didn’t deserve it. He was just a good person.”

Bob came home from Vietnam and the Army with one goal—to move on. In 1971, he resumed a job as a lineman for the telephone company, a job he held for 43 years. He also went back to college. But school didn’t last long. He didn’t have much in common with other students. He had grown in the service.

“I was more mature, more responsible,” Bob says. “I felt like I was among a bunch of kids and I had gone beyond them.”

He wanted to put his military career behind him, too. He got married and had three children. For a time, he met occasionally with former platoon mates who lived in the Chicago-area. But that ended after a while.

“When my military career in Vietnam was over, I put it in the back of my mind,” he says. “It was like, I have to let it go. I need to get on with my life. Maybe they felt the same way. I don’t know. We had to get on with our lives.”

Still, Bob has not been totally removed from his military experience. He belongs to a motorcycle riders group that sponsors events for veterans. Bob has even been on hand to greet veterans returning to Midway Airport from their Honor Flights to Washington D.C.

“I’ve talked with other vets who have gone on an Honor Flight,” he says. “They all tell me the same thing. They wish they could go again. That’s how much they enjoyed it.”

Bob’s trip will be special for another reason. He smiles when he tells me that his son is going along as his Guardian.

As I get ready to leave his house, Bob points out a picture of this three children, two police officers and a former police dispatcher. He tells me that his son-in-law is a police officer, too. And his brother is a retired officer.

“We’re kind of all patriotic kind of people,” he says proudly. “So that’s cool.”

Congratulations, Bob. And thank you. Here’s hoping you and your son share an unforgettable experience.