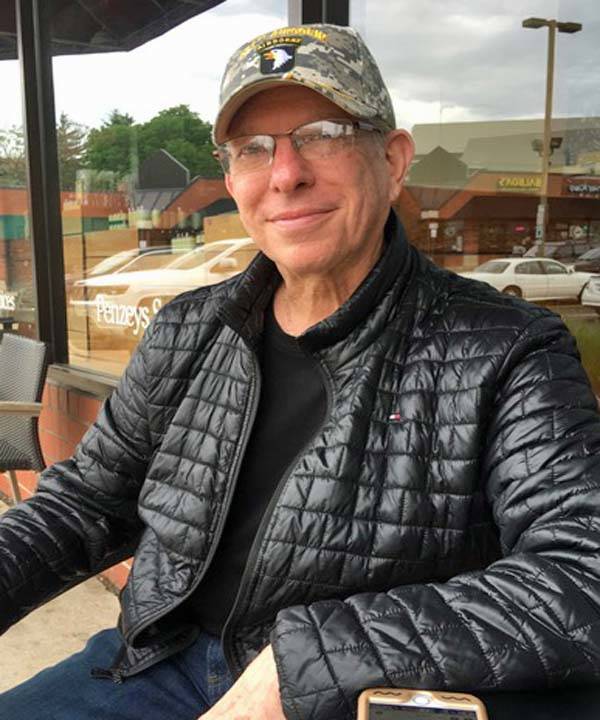

U.S. Army Vietnam Naperville, IL Flight date: June, 2019

By Wendy L. Ellis, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

Barry Greenberg will be the first to tell you that when it comes to Vietnam, he outsmarted himself. Half way through his second year of college, Greenberg dropped out and enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1968. It was not a decision popular with his parents back in the small southern Illinois town of Murphysboro, but at 18-years-old, he was pretty sure he knew better.

“I wanted to serve,” says Greenberg. “I had all the answers. I was 18 and knew everything.” Greenberg’s army recruiter suggested he sign up for military intelligence, since he demonstrated a real talent for foreign languages. Enrolling in Russian classes would get him sent to Germany, or so he thought. His rude awakening came when he was sent to Military Intelligence School in Baltimore, followed by 900 hours of intensive Vietnamese training at the Defense Language Institute in Virginia-the first sign he wasn’t going to Germany.

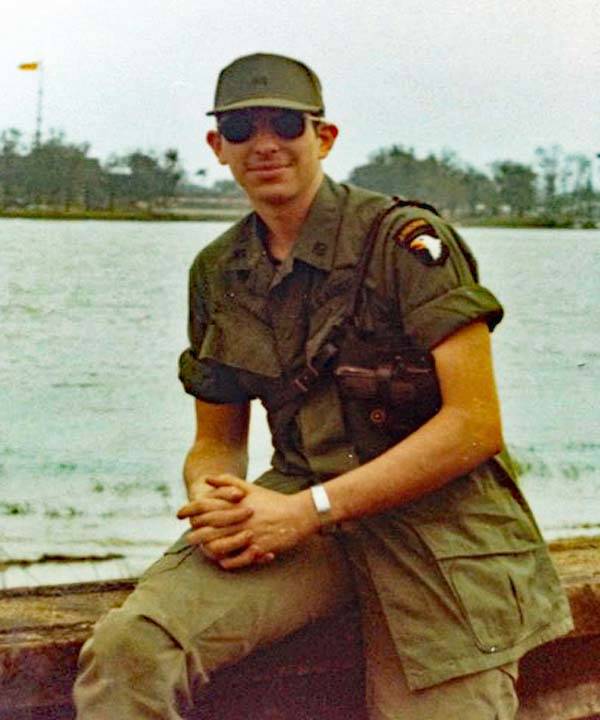

He arrived in Bien Hoa, South Vietnam, in June of 1969, in the dead of night, in the intense heat and humidity of a Vietnam summer. Greenberg was assigned to the 101st Airborne as an intel interrogator, specifically tasked with interviewing POWs in their native tongue. His new home was a hooch at Camp Eagle, 60 miles south of the DMZ. When U.S. troops farther north took a prisoner they thought needed interrogating, Greenberg would get the call.

“When we got called out we would take a UH 1 (UH-1 Iroquois is a utility military helicopter) out to a fire base where the interrogation would occur. And every time we went out we were required to take a South Vietnamese Army counterpart with us, who was also bilingual, so the team could discuss things. I think the tacit secondary vision was to test our counterpart’s trustworthiness. There were many South Vietnamese citizens, who sympathized with the Viet Cong communists. They were just as dangerous as the North Vietnamese Army regulars, if not more so, because they were not easily identifiable.”

During his tour of duty, the 101st Airborne didn’t take a lot of prisoners, so Greenberg found himself looking for other things to do. That’s how he ended up in Psychological Operations, or PSYOP for short. Every few weeks Greenberg would go up in a Huey helicopter with huge audio speakers mounted on each side. Speaking fluent Vietnamese, he would urge people hidden in the jungles below, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese alike, to come in, to defect, promising safety for them and their families. At the same time, he would drop thousands of propaganda leaflets on the landscape below. For a time, he was a U.S. Army version of that well-known North Vietnam radio propagandist, Hanoi Hannah.

Greenberg’s duties did not often put him in the line of fire, but there were some lucky, or unlucky, moments. A rocket attack on their living space destroyed a brand new jeep, incinerated the canvas roof, and tore part of their hooch to shreds. But Greenberg and his hooch mates were left untouched in a five foot deep trench only meters away. If the rocket’s shrapnel had a different trajectory, the end of the story would have been far different.

And then there were those unexplainable moments. “On one of the days, toward the end of my tour, I was assigned to go interrogate a POW,” says Greenberg. “I had to fly a helicopter out to the firebase to do so, diverting from my previously scheduled PSYOP mission. When I returned to Camp Eagle, my commanding officer came up to me and said, ‘Have you got the luck of the Irish. Your PSYOP chopper was shot down today. The pilot took a bullet in the leg but they saw where the muzzle flash came from and were able to call for evacuation and backup.’” Despite severe damage to the chopper, the crew was able to maneuver themselves far enough away, giving time for two gunships and a rescue ship to keep the enemy at bay and complete the evacuation successfully.

Moments like that, all these years later, still have Greenberg shaking his head in amazement. His tour of duty might have lasted longer, but he was called home suddenly upon the death of his sister. The news, and his departure from home, were so sudden that he left all his gear behind. Twenty-seven hours after getting word, he arrived at his sister’s funeral in shirtsleeves in the dead of winter. He was not sent back to Vietnam. He served in other capacities stateside until he was discharged from the Army in 1971; he returned to college, this time at Southern Illinois University, near home and his parents.

“It’s amazing how smart they became while I was gone,” laughs Greenberg. “They were brilliant!” His major of political science and international relations led him on to law school at Northern Illinois University, and 40 years later he is still practicing law, for the past 20 years in Naperville. He has been married to his wife Mary Fran for 25 years, raising three children.

In 1984, Greenberg took on a case that ended up changing Illinois law. A young unmarried woman with a 26-month-old child wanted child support from the child’s father, although he did not admit paternity. At the time, Illinois law said a parent of an illegitimate child had only 24 months to request support, while a parent of a legitimate child had 18 years. Greenberg challenged the law as unconstitutional, eventually arguing the case in front of the Illinois Supreme Court in Springfield. He and his client won the case, and not long after, the Illinois legislature changed the law so that all children, legitimate or illegitimate, hold the same legal rights under the law.

A copy of that ruling hangs on his office wall. Also hanging on his office wall is a frame full of medals awarded during his years of service. Like many veterans, he is reluctant to boast of what he achieved but among them are the Army Air Medal, the Army Commendation Medal, and the Good Conduct Medal. While he has long admitted that he didn’t know everything when he was 18, he does say, “Joining the military was the best thing I ever did for myself, and if called, I’d go again.”