U.S. Army Korean War Chesterton, IN Flight date: July, 2019

By Al Rodriguez, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interviews Volunteer

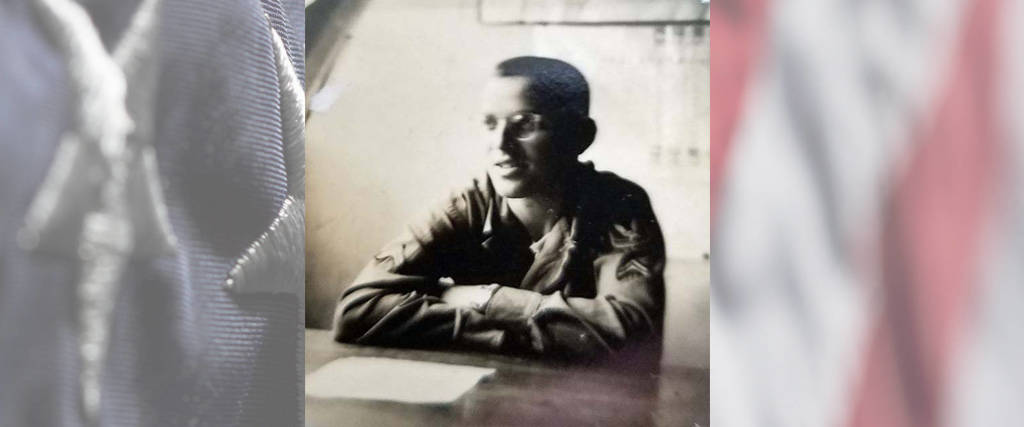

On his Honor Flight application, Mr. Yates states he was an Army photographer in Korea, an understatement indeed. This was certainly confirmed by the many framed, beautiful images displayed in his home that he had photographed throughout his life, foremost from Korea. Photography was the gateway to the movie and television career Ascher had after his Army commitment.

Ascher was born in Long Island, New York, in 1931. His grandparents were Russian immigrants that came to this country in 1903. His parents were vaudeville performers that traveled the circuit between New York City and Chicago. One of his early memories was the packing and unpacking that went along with all that traveling. At 7, they moved to Los Angeles, California. One of his hobbies growing up was photography. He completed high school and studied at UCLA until being drafted by the Army in 1952.

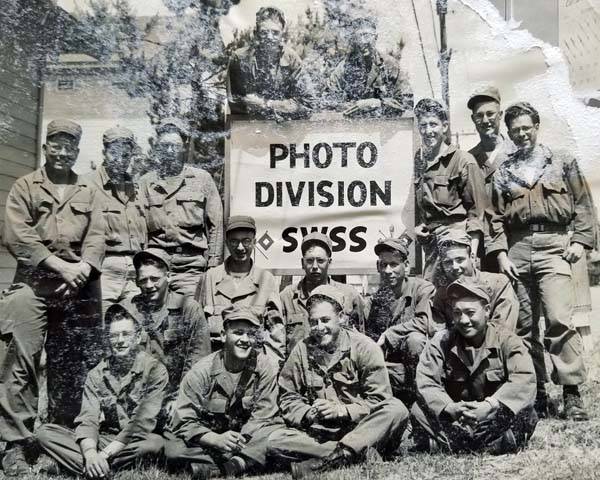

He was sent to Camp San Luis Obispo for Basic Training in November, 1952. During the Korean War, the camp was used by the U.S. Army for Signal Corps training which was eight weeks of basic combat training and then technical classes covering all aspects of the Signal Corps, from lineman and teletype, to cryptography. After Basic, he stayed at Camp San Luis Obispo for photography school.

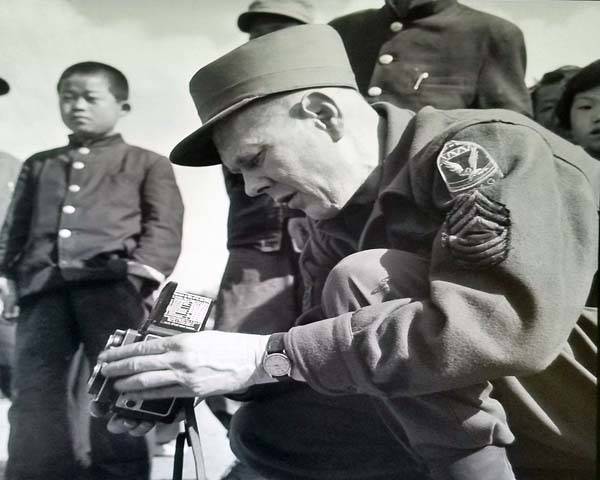

He was sent to Korea in February, 1953 joining the Korean Military Advisory Group/Signal Corps in Taegu, South Korea. This is where he met Master Sergeant Kaye, a 30-year photographic artist and “curmudgeon.” Kaye asked for Ascher’s portfolio, then proceeded to tear his pictures up. It went downhill from there; verbal hell is how he described it. Because of Kaye’s insistence on excellence, Ascher credits Kaye for teaching him to be a decent photographer and artist. He learned on the Army camera of choice, a 4-by-5 large format speed Graphic camera. It weighs 6-to-7 lbs depending on accessories. He also carried 24 film holders and 24 flashbulbs in his pack which weighed 50 lbs. There was no room for a weapon. He would be flown into combat areas on a de Havilland L-20 Beaver plane. Once there, he would walk with the infantry to the front lines to photograph terrain, enemy weapons and emplacements, gathering intelligence for the military. The war ended July of 1953, but he stayed in Korea another year. He was assigned to the KMAG, the Korean Military Advisory Group, training Korean soldiers in the art of photography. Like so many other veterans when asked his thoughts about Korea and the Army he simply said “I did as I was told.”

After arriving back in Los Angeles, he was employed at the UCLA Medical Center as a medical photographer. After a year, a doctor handed him a movie camera and asked if he could film surgical procedures. He immediately said yes, even though he had never operated one. He immediately started a crash learning course by practicing with this new type of camera. According to Ascher, “after still pictures, moving pictures were an exhilarating experience.” The first movies were silent, but the doctors soon insisted on sound.

After arriving back in Los Angeles, he was employed at the UCLA Medical Center as a medical photographer. After a year, a doctor handed him a movie camera and asked if he could film surgical procedures. He immediately said yes, even though he had never operated one. He immediately started a crash learning course by practicing with this new type of camera. According to Ascher, “after still pictures, moving pictures were an exhilarating experience.” The first movies were silent, but the doctors soon insisted on sound.

Ascher married and had a son Julian in 1960. He bought his first house using the G.I. Bill. He also re-enrolled in UCLA, changed his major from pre-med, and received a Bachelor’s Degree in Theater Arts/Motion Pictures. His first job out of college was at KTTV in Los Angeles as a film editor. In 1972, he found work at Universal Studios in the movie and television departments. In 1977, he married his second wife, Elaine, who had children from a previous marriage. His stepdaughter went to Northwestern University, married, and stayed in the Chicagoland area.

Ascher won a 1983 Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Sound Editing in a Limited Series for The Executioner’s Song that aired on NBC in November 28-29, 1982. He’s prouder of the two Golden Reel awards he received from the International Guild Awards because they were presented by his peers. He received one in 1978 for a Battlestar Galactica Special and in 1985 for an Airwolf ‘Eagles’ episode. He and his family lived in Woodland Hills in the San Fernando Valley when in 1994, the Northridge Earthquake devastated their neighborhood. They did rebuild; Ascher and his wife retired in 1995.

Retirement started them thinking about moving away from L.A. With a daughter and grandson in Chicago, and no earthquakes in the midwest, they moved to Chesterton, Indiana. Sadly, his wife Elaine died in 2007. Ascher worked part-time at the Chesterton Public Library until 2015. He also volunteers at the Indiana Dunes National Park. Ascher was honored by Valparaiso University which recently exhibited his Korean pictures. To maintain his skills with his old Graphics camera, he took a ‘non digital’ photography class at Valparaiso University this past winter. Ascher feels that using a film camera is out of fashion so he thought he would take the class before it is no longer offered.

In 2015, a friend talked to Ascher about Barbara, someone he thought he should meet. The friend gave Ascher her number but he vacillated and didn’t make the call. Two months later she called him. They recently married on June 23, 2019, in the backyard of the house they share. Ascher says “We had one hell of a great wedding and party afterwards in spite of the rain. My point and shoot digital camera was the only casualty. It had too much champagne, suffered a severe hangover and died from lack of battery power. I went online and bought a replacement. When it arrives, I’ll have it stand at attention, lens front, shutter closed, battery power open and give it verbal hell.”

Ascher is looking forward to going to D.C. with his military colleagues who shared similar experiences.