Army Vietnam War Flight date: 10/23/24

By Joe Kolina, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

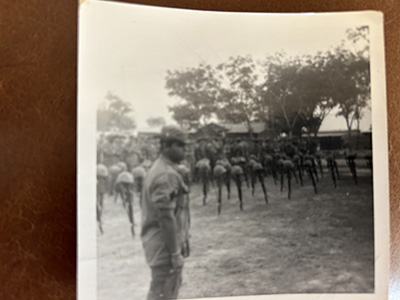

The small black-and-white photograph has faded with time, but now it means even more to Frank Gillie Jr.

He picks it up carefully and holds it reverently in his cupped hands, as he shows it to me.

A burly soldier stands somberly in the foreground, a strong, stoic sentry. His face looks ahead solemnly, his arms dangle at his side. Behind him, under a small, leafy grove of trees, is a jarring sight.

There are row after row of rifles. They stand mutely upside down, their bayonets thrust deep into the earth. Helmets perch atop the M-16s.

“The first operation that I went on after I got to Vietnam was called Operation Saratoga,” Frank tells me softly. “We were out in the woods for 89 days. That is the ceremony we had when we got back to base camp. Each one of those M-16s with a helmet on it represented a man who was lost in action.”

There were 71 rifles and helmets. Frank pauses, and looks away. Tears well in his eyes as he recalls February, 1968, when he was just 20 years old.

“That picture is very special to me,” he whispers.

War was the last thing on Frank Gille’s mind just a year earlier in his hometown of Chicago. He was working part-time at the post office and dreaming about going to college at Tennessee State University in Nashville. He and a friend had visited the school. They were impressed by the sophisticated, dashing young men who drove around campus in their own cars.

“I said damn, that’s what I want,” Frank recalls with a hearty laugh and a big smile. “I thought if I could work at the post office another six months I’d have enough money to buy a car and hit campus right.”

That’s not how it worked out. He got a draft notice instead. In May, 1967 he began basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. Mortar training followed at Fort Polk, La., commonly known as Tigerland.

“If you went to Tigerland,” he says,” your next stop was Vietnam.”

Before he knew it, Frank had landed at the Army base at Cu Chi, a rural district 30 miles north of Saigon. In just weeks, Cu Chi would become known around the world for a vast tunnel system that the Viet Cong used to help launch the Tet Offensive.

“I processed in, got a bunk, a rifle and a night’s sleep,” he says. “The next morning we shipped out.”

Operation Saratoga was just the beginning of Frank’s year on the firing line. The Army classified him as an 11C. The C meant he was part of a mortar crew. The 11 meant he was first, and foremost, an infantryman.

“At first, I thought, mortar support, yeah, that’s a pretty good position, maybe it won’t be so bad,” Frank remembers. “But anything with an 11 on it makes you straight infantry. So we did what the line dogs did. We went on sweeps, we went on ambush patrols, we got dropped into hot landing zones.”

One of those patrols led to the action that earned Frank his first Bronze Star. A fellow soldier was hit in heavy fire.

“He was down, he was down,” Frank says,” and you don’t leave nobody. So we got the order: go in and get him.”

Three soldiers began the arduous rescue. Withering gunfire whizzed around and over them. But slowly, they crawled in the dust and dirt down a narrow trail toward the wounded man.

“We did it the textbook way, just like we were taught,” he recalls. “Fire and move. Fire and move. Two of us fired, and the third one crawled a little bit forward. And we just kept inching up, closer and closer.”

What goes through a man’s mind at a moment like that?

“I gotta throw some lead. I gotta keep throwing lead,” Frank remembers thinking. “We got to keep the fire going. You run out of a clip, you put another clip in. You just got to keep firing.”

Finally, one of them crept close enough to grab their wounded comrade.

“Then we really opened up to give them cover, to drag him out,” Frank says, adding quietly, “He didn’t make it. But we fought our way in, and fought our way out, and brought him back.”

Manning mortar positions carried its own risks. Frank found that out in a hair-raising episode he still finds “kind of funny.” It resulted in his second Bronze Star.

The very unpopular sergeant-major of his platoon ordered them to set up camp. He told them they would likely stay there for a while. So the platoon dug a huge hole for ammunition. They stored the ammo for his whole company there.

“Suddenly we got bombarded,” he says. “One of the rounds hit the side of that hole. All that ammo was in danger of blowing up.”

The sergeant-major sprang into action.

“He got some buckets of water and ran over to that hole,” Frank remembers. “He’s trying to pour water in there. And for some reason, instead of running away, I ran over there and started helping him pour water on all that ammo. And we put that fire out.”

Some of the other men in the platoon came up to him, heads shaking, asking why he ran to danger instead of protecting himself.

“He don’t like you, and you definitely don’t like him. Why did you do that?” they asked Frank.

“I don’t know to this day,” he answers. “Because we could have very well both been blown higher than the Willis Tower if that dump had gone up. But that same crotchety old guy gave me a Bronze Star for that.”

The most long-lasting physical effect of serving in Vietnam didn’t have anything to do with firing guns or mortars.

“I had jungle rot in my feet,” he says. “I walked in a lot of rice paddies. Walked in a lot of muck. My feet stayed wet for so long that when I finally got back to base camp, and I took my boots and socks off, my toenails stuck to the inside of my socks.”

They’ve never grown back normally and he still requires a podiatrist for special foot care.

“I don’t wear sandals. I don’t wear flip-flops,” he says with a wry shake of his head.

When Frank got out of the Army in 1968 he returned to Chicago and the post office, then became a steelworker at the giant South Works plant, and a city building inspector before serving for 32 years as a Chicago firefighter.

Frank still hesitates to talk about his Vietnam experiences, especially in public, even now after so much time has passed.

“I’m not a war story person,” he says, “even though you never forget that stuff.”

But he’s proud of his participation in the Vietnam Veteran’s Parade down Chicago’s world-famous Michigan Avenue in 1986.

“I was so proud that my unit—the Wolfhounds— led the parade with General Westmoreland,” he says. “It was such an honor, such an honor.”

The parade was also significant for a personal act of reconciliation. The parade ended at the site of the traveling Vietnam Veterans Wall. As Frank gazed at the wall, and all those names, a man approached.

“And this man says you’re Frank Gillie, aren’t you,” he says. “You don’t remember me, do you?”

It turns out he was a man named James, a fellow solider he had tangled with in Vietnam. James had travelled from down south to attend the parade with his wife and family.

“I once tried to crack his head open,” Frank says. “Now he was standing there, and we started talking and laughing. And we hugged and we stood there crying.”

Frank now looks forward to visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial during his Honor Flight to Washington, D.C. He’ll be looking for one name in particular among the more than 58-thousand names etched into those big, black granite walls.

The name belongs to a man named Kenny Kolter, from North Carolina.

“He’s always been in my spirit,” Frank says. “He was one of those bubbly little guys. He had this little skeeter head and his helmet always flopped over his head.”

Frank and Kenny were in different companies but often camped near each other. Kenny came over for food and beer and companionship.

“He was a little guy, funny as hell,” Frank says. “He went out on ambush patrol one night. And out of that platoon of 30 men only five came back.”

Kenny Kolter was not one of them.

“His name has stuck in my head all these years,” he says. “So I’m going to look up Kenny Kolter.”

Good luck, Frank, and congratulations on your selection for an Honor Flight.

Thank you for your service, and Welcome Home.