Army Vietnam War Downers Grove, IL Flight date: 07/24/24

By Mark Splitstone, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

John Wander was born in 1941 and raised in Downers Grove. His parents were both the children of immigrants, and they both faced significant challenges when they were growing up. Neither of them graduated from high school, but they always managed to provide a safe and secure home for John and his sister. They also ingrained in them the value of hard work, an appreciation of the opportunities afforded by their country, and the importance of family. John graduated from high school in 1959 and then attended the University of Illinois in Champaign, where he began as a pre-dental major before switching to pre-med. After three years as an undergraduate, John was accepted into the medical school at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

The “Berry Plan,” implemented in the mid-1950s, allowed doctors to defer obligatory military service until they completed medical school and an internship. For John, this plan allowed him to graduate from medical school in 1966 and complete a surgery internship in 1967 before joining the Army. While many men in his position tried to avoid military service, John looked at it as part of an obligation to his country for all the opportunities he and his family had been afforded in America. In July 1967 he joined the Army as a captain and drove to Fort Sam Houston in Texas for a specialized basic training designed solely for physicians. In addition to all the training that non-physician soldiers were required to do, John and his fellow doctors had classes to learn about things such as infectious diseases that they might encounter overseas.

After basic training, many of John’s fellow doctors were sent to Vietnam, where US involvement was nearing its peak, but John was stationed in South Korea. He served as the command surgeon at a 600-man army base eight miles south of the DMZ near the town of Chuncheon in the Kangwon province. He was in charge of a 12-bed clinic with a small operating room and lab. It was staffed by John, two other doctors, two dentists, and some lab technicians. The medics who worked with the clinic were very good, and John always tried to find ways to teach them new skills and increase their responsibilities.

While the Korean War had been over for fourteen years, the area around the DMZ still saw frequent violence. The nearby Korean Army base reported that they killed about fifty North Korean infiltrators a month. Tensions rose even higher in early 1968 when the Tet Offensive occurred in Vietnam while at the same time, North Korea captured a US ship, the USS Pueblo. John’s base was placed on high alert as the North Koreans massed their armies at the border. John knew his base would be a major target if there was an invasion because it contained nuclear-capable “Honest John” rockets. Fortunately, there was no invasion, but the base was still a dangerous place. In his thirteen months in Korea, seven men out of the 600-man base died, usually because of vehicle accidents or other mistakes.

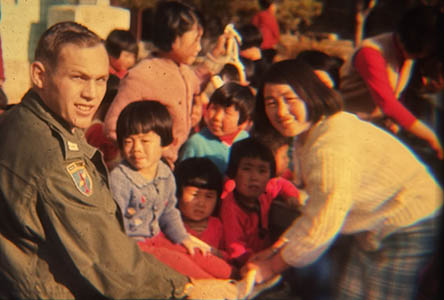

When John first arrived in South Korea, he treated only American soldiers and Koreans attached to the US Army. Over time, though, his responsibilities increased. There were a number of orphanages in the area, and the engineer group at the base had started a program whereby they would save up leftover food over the course of the week and then on Sunday eight children from the nearest orphanage would come to the base and eat. One time, a girl from the orphanage fell and split open her chin. They took her to see John, who cleaned the wound and stitched her up. Unfortunately, the wound later became infected and John had to treat her again. He tried to explain to her caretakers that they needed to clean the wound with soap and water three times a day and periodically change the dressing. After they left, John’s Korean aide, skeptical that the orphanage would be able to follow his instructions, suggested that he go and see the orphanage. It consisted of a small, barely-heated room, and all eight kids slept on the floor. They got their water from a nearby hand pump and ate rice harvested from a paddy fertilized with human waste. John immediately realized the futility of trying to keep a wound clean in these circumstances. American-style hygiene just wasn’t practical.

This was the origin of a program designed and managed by John. It started as a Sunday afternoon sick call for that orphanage but eventually expanded to daily sick calls for five different area orphanages. His clinic would treat American and Korean soldiers in the morning, and then have sick calls for the orphanages in the afternoon. When the program expanded to the point where he needed money, he tried to get approval from his superiors. There seemed to be confusion about the program because nobody had ever tried something like it before. Eventually, it was decided that he could spend the money as long as the request was made in writing and as long as the command surgeon of the base approved it. Since John was the command surgeon, he simply sent a request to himself and then he approved it.

He treated ailments with the children of Korea that he never saw as a doctor in the United States, such as tuberculosis, roundworm, hookworm, and polio. The polio was so common that John decided to request 500 doses of the Sabin oral polio vaccine. The army ended up shipping him 5,000 doses, and he and his team went out to the orphanages and the wider community to administer them. John received awards from Korean government officials to thank him for his work, as well as an army commendation. He estimates that in the time he was in South Korea, he treated as many Korean patients as Army personnel. Occasionally, a patient was in a condition that John was unable to treat with the limited resources in his clinic. He’d then take them to a hospital and pay the bill out of his own pocket. By the time he left South Korea, he calculated that he had spent about twenty percent of his salary on Korean patients.

After thirteen months in South Korea, John returned to the United States and was stationed at Fort Leonard Wood, where he got a great deal of experience performing orthopedic surgery. When his enlistment was up, the Army gave him opportunities to stay longer, but he wanted to start his surgery career so he left in June 1969. He returned to Chicago and did four years of surgical residency and three years of surgical oncology before moving to a private practice. He eventually retired in 2012, at age 71, after a long career of medicine and teaching.

John and his wife Ruth had four children, all born within a three-and-a-half-year time period. In 1981, they bought a house in Downers Grove that had been built in 1893 and is just six blocks from the house he grew up in. They’ve spent a lot of time in the last forty years renovating and maintaining the house and in 2017 it was officially designated as a historic landmark by the Village of Downers Grove. While he says that it’s exhausting to keep up with maintenance on it, the house is considered to be the family home and is a magnet for other members of the family. Of his seven grandchildren, five of them live nearby, and he and Ruth get to see them often.

In addition to spending time with his children and grandchildren, John likes to visit his cabin in Wisconsin and also enjoys playing what he calls “not-so-great golf.” He had a long and impressive career in medicine, but he says the most satisfying thing he ever did was treat the children of South Korea. His memories of that time are “marvelous.”