Army Vietnam War Flight date: 04/10/24

By Lauren Jones, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

“Fantastic” is how Mike Ryan describes his experience on April 10, 2024, when he traveled from Chicago to Washington, D.C., as a respected guest of the Honor Flight Chicago program.

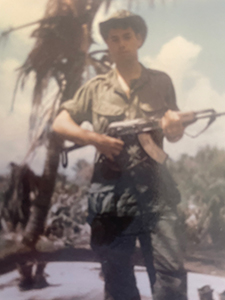

Mike was recognized for serving as an Army Sergeant from July 1967 to July 1969, serving a year in Vietnam as part of the Combat Infantry Division. Mike received a Purple Heart for an injury he suffered during his service.

“I was so impressed at the Honor Flight. You get there at 4 o’clock in the morning, you know, and they put you in a wheelchair even if you can walk. There were no chairs when we were all lined up in there, so yeah, I needed the chair.”

He continued, “They must have had at least 200 volunteers in there. Some are even veterans, and they all treat you fantastically. It put my faith back in the human race.” Mike especially enjoyed hearing Wayne Messmer sing the National Anthem.

Once in Washington, D.C., he said the police escorts helped to ensure they stayed on time. “We saw Arlington National Cemetery, the Lincoln Memorial, and the World War II Memorial. We got close to the Washington Monument and saw the Korean War Memorial. My daughter loved the Korean one. And, of course, I saw the Wall.”

Mike was escorted by his daughter, whom he describes as a history buff. “I’m glad that we got to experience this together. She’s a good kid who helps me a lot,” he said proudly. Overall, he couldn’t believe how friendly everyone was, even the volunteers at Dulles Airport who helped them safely get on their flight back to Chicago.

Mike’s whole family was at Midway Airport to welcome him home.

The Tet Offensive

Mike was drafted in 1967 at the age of 20. He was serving the first year of his pipefitter apprenticeship. “At that time, we were supposed to be exempt, but they needed so many people over there that they took the exemption away. So, I got drafted.”

He was initially drafted at the age of 19, but his father passed away, so he got a one-year exemption. He was not interested in the service and went in “grudgingly.” Mike started his service in basic training at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. He was then sent to Fort Polk in Louisiana for infantry and jungle training called AIT, or advanced infantry training.

His next stop after training was the Bien Hoa Air Base in Vietnam. Mike arrived on Jan. 1, 1968. He received a uniform and was assigned to the 9th Infantry. They started in the middle of the country, which is all jungle. “It was quiet and I had no idea what I was getting into. I had no idea. I thought the training was bad, you know. But it was nothing compared to what I actually got into. I was in heavy combat quite a bit.”

Mike was in Vietnam for about two months when the Tet Offensive began on Jan. 30, 1968. The Lunar New Year, or “Tet” holiday, provided North Vietnamese soldiers and communist Viet Cong forces an opportunity to surprise targets in South Vietnam. Although the Tet Offensive ended in April as a military defeat for the communists, thousands of U.S. soldiers lost their lives and were wounded.

“They attacked because they thought everyone was going to be celebrating,” Mike explained. “Excuse my language, but that’s when shit hit the fan. Instead of just fighting the Viet Cong, we’re now fighting regular Army soldiers from the north. They were much more well-equipped. We were there for a while; then, they moved us down to the Mekong Delta area, which is the southern part of Vietnam. Saigon was hit pretty hard in the offensive.”

According to the National Archives, 1968 was the bloodiest year of the war for the United States. 16,899 Americans were killed, which is nearly 30 percent of the total American deaths in Vietnam.

“We were always on guard.”

The unit Mike served in conducted search and destroy missions. “Our unit was always searching, always on the move. I never had a central base camp. Helicopters would come in, pick us up, and fly us to a territory that we would then sweep through and search. We got into a lot of battles that way. We were always on guard.

“It wasn’t as bad as the Tet Offensive because everything’s a little more open as we went through the small towns. But the Viet Cong would hide in buildings. They don’t have big buildings like we do, just one-story buildings. You could hear the bullets whizzing right by your head. They were hiding, and we just had to keep going.

“We didn’t want to leave any of the deceased behind, so we would carry them. But rigor mortis would set in, and their body was stiff. Oh God. But we were just trying to get them home. That’s all we did was search and destroy and fight. That’s it. You know, we were looking for them. They were looking for us. We were always on the move.”

Mike’s unit couldn’t shower often, and they could only relax when they went to an artillery base. They felt a little safer since that’s where the big cannons were. But Mike was always alert since “they can throw a mortar in and hit you no matter where you’re at.” So there was no “safe” place.

Since they didn’t have a base camp, the unit would carry whatever they had, including food. “We slept right on the ground,” he explained. “Just say alright, we’re going to stop here for tonight, and that’s it. To keep watch, say you have 50 guys in your company. Out of those 50 guys, you would send out what they call an LP (listening post), and there could be four guys in that LP. During the night, each guy takes a turn. And he would stay on watch in case somebody tried to sneak up. So, everybody would take about two or three hours and then wake up the next guy.

“We didn’t dig foxholes or anything like they did in World War II since we weren’t there that long. We were always looking and searching.” During his service, Mike was able to get a week of rest and relaxation in Hawaii. One week and right back.

Purple Heart

One night, about eight months into his time in Vietnam, Mike’s unit was setting up an ambush. It was right before dusk, and everyone was in single file. The soldiers went out about 500 feet when they were ambushed. Mike was shot in his left calf. He had to wait all night before being taken to a medical facility in the morning. “They won’t come in and get you because it’s nighttime. They’re not going to fly at night to rescue you. It’s too dangerous.

“So, the medic put a bandage over the wound, and I stayed in a canal all night. By the next morning, the wound didn’t hurt much, but it was itching me like crazy. So, the medic took the bandage off, and I had a leech the size of a banana on there, sucking the blood. The medic did his best in the dark, but the bandage must have had a leech on it. They’re in the water over there.”

Mike was sent to a base unit for an operation and didn’t realize he’d need to be awake for the procedure. “The doctor localized the anesthesia, but he didn’t put me out. I asked and even told him I’d enjoy it, but I was awake the whole time. I remember the feeling that he was cutting into me like meat. The bullet struck me on the side of my leg and came out the other side. It missed my bone by half an inch.” Mike has experienced dead nerves in his leg since the incident but feels lucky to have his leg. He was awarded a Purple Heart to recognize the wound he received while in action.

During his time recuperating at Cam Ranh Bay, Mike developed an appreciation for the beauty of Vietnam. The doctor had him clean his wound in salt water so he would go to the beach every day. While there, he would look around and think, “These people here are crazy. They can make such a vacation area! And now they have.”

Mike also saw a man get wheeled into the base with the inside of his whole upper thigh exposed, down to his femur bone. It was clearly not a normal gunshot wound or even from shrapnel. The man was alert, so Mike asked what happened. The man told him that, unfortunately, he was an LP who fell asleep. So a tiger was able to sneak up and bite him, trying to drag him away by his thigh. “Everybody’s up now!” Mike joked. But the man was fine and didn’t suffer severe infection.

Although he didn’t encounter a tiger, Mike dealt with lizards that grew to six feet long, pythons, and wild boars. He said the mosquitoes were so terrible at night that he kept his netting on. He described the boar as especially alarming: “You’d hear them running at night because that’s when they hunt. So, you don’t know what was coming at you. Is it the enemy or what? And you’d have to think about that as you tried to sleep.”

After about five weeks of recovery, Mike returned to his regular patrol and had about four months left in Vietnam. He kept a few countdown calendars, as did other soldiers. “It’s very psychological,” he explained.

“I made it.”

One particularly difficult day was his 21st birthday. “On my birthday, we were on patrol and hit the edge of a jungle. It’s kind of a semicircle type of thing. We’re coming in there because we know Viet Cong is in there, when all of a sudden, they hit us badly.

“As soon as you hear one gunshot, everybody’s down. So now we’re in the rice paddies and mud. They had us pinned down so we could not move. They were just firing. We were stuck there all day, running out of food, ammunition, and water. We didn’t want to be there when it got dark because they can move through the jungle much better than we can. We’re noisy when walking because we have everything like canteens and helmets. All they need is a bag of rice and a rifle.

“They were going to overrun us,” he continued, “so our leaders finally called in the jets. We’re only talking a few hundred feet between us, so we hid in the berm for almost 20 hours. And finally, the jets arrived and dropped their bombs. We got out of there.”

The last month Mike was in Vietnam, a job opportunity opened for him to be a Jeep driver for officers as they traveled to different base camps. A few guys applied, and Mike feels lucky to have gotten the position. “I only had four weeks left. And, you know, you’re nervous all the time anyway, but you really start getting nervous when it gets close. I might make it or not. I saw a lot of people get killed. Four weeks. Am I going to make it?

“So that job helped me basically get out of the combat area. I felt slightly safer but didn’t feel complete relief until my flight home. On my last day, I checked out and got on the airplane. As soon as the wheels left the ground, I felt such relief in my body,” he states emotionally, clearly remembering the feeling. “I made it.”

After serving in Vietnam, Mike served six months at Fort Benning, GA (now Fort Moore), training soldiers preparing to leave for Vietnam. He was on a demolition crew, working with dynamite to simulate mortar attacks.

“They love the tiger story.”

Upon returning home, Mike took a few weeks off and returned to being a pipefitter. He feels lucky to have had a job that kept him busy and his mind off Vietnam. He talks more about his time in Vietnam now than he did when he first returned home from the war.

He has also spoken to students at various schools to tell his stories. “They love the tiger story and wonder how there’s no McDonald’s out there,” he said. Mike laughs, thinking about the kids who are so curious about how he pooped in the jungle.

Mike and his wife Diane of 50 years enjoy being close with their four children who live in the area and their 10 grandchildren. His priorities are seeing the grandkids play sports and participate in various competitions, and playing golf whenever he can. He also belongs to the American Legion, which donates to a lot of veteran organizations.

Thank you for your service, Mike! We are so glad you enjoyed your well-earned and much-deserved Honor Flight experience!