Army and Marine Corps Flight date: 04/10/24

By Joe Kolina, Honor Flight Chicago Veteran Interview Volunteer

Major John Ashford knew he was in a bad situation on that dangerous day in Bosnia in 1996. What he didn’t know was how fast it was going to go from bad to worse.

Major Ashford was an Army Reserves Civil Affairs officer in Bosnia as part of the multinational peacekeeping force sent to implement the Dayton Peace Agreement. Their job was to help ease tensions after the war spurred by ethnic animosities in countries that were once provinces of what had been Yugoslavia.

On that day he joined officers from Ukraine and France looking for anything suspicious in the hills around the rural village of Pale, southeast of the capital city of Sarajevo. It was a dangerous job. They came upon wandering groups of people and had to decide instantly whether they were armed and dangerous, and what to do about them. One group of 8 to 10 men were clearly special forces soldiers, who could not explain what they were doing there.

“I approached and spoke to them in my broken Serbian,” Major Ashford recalls. “At first they were nice to me. They said they were glad Americans had come to Bosnia. But when I told them they had to go, they stopped smiling.”

The soldiers suddenly surrounded him with rifles raised, all pointing right at him.

“I thought, okay, if I can get my gun out I can kill one or two. But there was no way they were going to let me do that,” he remembers with a sad shake of his head. “I thought: I’m going to die.”

Suddenly, he heard the rumble of an armored personnel carrier. It roared down the road toward him and then screeched to a stop. A young American officer, rifle at the ready, stormed out of the vehicle and led a squad of heavily armed soldiers as they rushed toward him. They quickly surrounded the menacing special forces unit, which laid down its’ arms and surrendered.

“He said don’t worry Major Ashford, we’ll take it from here,” he says with a broad grin and big laugh. “And I thought, I’m going to live after all.”

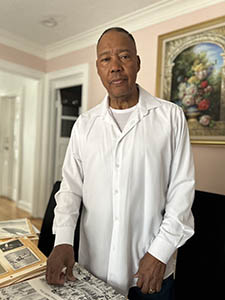

It’s just one unforgettable moment in a 26-year military career. A remarkable rise that began as an 18-year-old Marine Corps volunteer and ended as an Army Reserves Major. It’s a quintessentially American story that begins 74 years ago in grinding poverty in rural Alabama.

“We didn’t have a front door,” he says,” no lights, either, no nothing.”

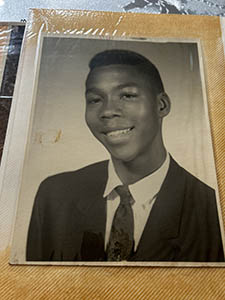

His father moved the family—his mother, a sister and him—to Evanston, Illinois when he was 9 years-old. He was a talented gymnast at Evanston Township High School, top-ranked in the state on the horizontal bar in 1966. Major Ashford was a 19-year-old theater major at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign when he decided to join the Marine Corps in April, 1969.

“I loved John Wayne in the movie Iwo Jima,” he says.” I wanted to be a Marine, the proud and the brave. A hero willing to fight and die for the flag. I was a patriot.”

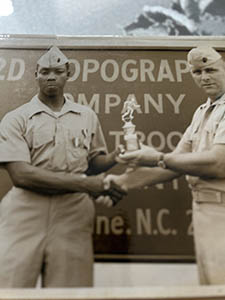

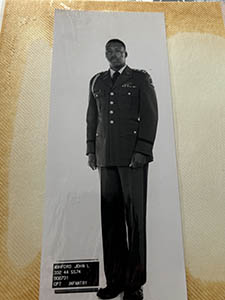

Photographs of Major Ashford from that period show a slender, smiling teenager developing into a ramrod straight recruit decked out in his Dress Blues, to a fully formed marine with a look of serious and focused concentration.

He completed basic training as a squad leader at Camp Pendleton, near San Diego, with his PFC stripe in 1969. “They called us Hollywood Marines,” he says, due to their proximity to Los Angeles. “But I learned in the Marines that you don’t do your job because they’re going to pat you on the back or pay you. You do your job because it’s your job.”

His service included MP duty at Patuxent Naval Air Station in Maryland, and a posting at Camp Lejeune, in North Carolina. Despite requesting duty in Vietnam, he was stationed for 18 months as a supply clerk in Iwakuni, Japan, 600 miles southwest of Tokyo, before leaving the Marines in 1972.

He would have to wait to fulfill his ambition to serve in a war zone. It was a journey that included some unexpected twists and turns.

Major Ashford got his college degree in Theatre at the University of Illinois Chicago in 1975. He gave acting a try in Chicago and Los Angeles, working jobs like security guard at night so he could audition for roles during the day. When his father died he switched careers to help out his family, working in Chicago as a case worker at the Illinois Department of Public Aid.

“But I still wanted to see the world,” he says. “And I still wanted to become an officer.”

So in 1979 he joined the U.S. Army, after the Marine Corps told him he would have to wait years for the chance to become an officer. It was off to basic training—again—this time at Fort Benning, Georgia. He won a physical training award and qualified for Officer Candidate School. Now a second lieutenant, he followed that up with Ranger School in 1980.

“We learned the basics of infantry,” he says describing the rigorous combat training as well as intense psychological, emotional and physical training. “You get in shape there, no way around that.”

Jump School was next, which he describes with a chuckle as “a piece of cake, except for the jumps.”

Major Ashford remembers his first jump as though it was yesterday. He recalls the extreme noise when the back door of the C-130 was opened, and the rush of the cold air that smacked his face as his name was called.

“Lieutenant,” he remembers the instructor bellowing, “stand-up and hook-up.”

He shakes his head as he describes standing there, wondering what he had gotten himself into.

“I am not a religious man,” he says, “but I thought to myself, ‘God, before I let the rest of these men think I’m scared, I’ll jump out of this plane without a parachute.’”

He shuffled to the door, glanced at the other trainees over his shoulder, and jumped.

“I tucked and counted one-one-thousand, two-one-thousand, three-one-thousand,” he says. “I pulled the cord, the parachute opened, I floated down, and I said, ’Thank you God.’”

Major Ashford spent most of the next three years as a platoon leader stationed in Mannheim, Germany. He joined the National Guard after leaving active duty in 1982, first in Washington, D.C. and then back in Chicago, where he resumed his career with the Illinois Department of Public Aid.

“It was a good experience,” he says. He rose to company commander and was promoted to captain, but something was missing. “I still had the urge to travel. So I made a change.”

It was a decision that led to the most dangerous, dramatic and interesting years of his service. He joined the Army Reserves in 1988 and was assigned to the 308 Civil Affairs unit. He promoted to Major in 1994 and sent to Bosnia in 1996.

The duty was difficult. It followed bitter fighting that killed 100,000 civilians. An estimated two million people were forcibly displaced.

“Our job was to talk to the locals,” Major Ashford says,” to find out what they needed. Then we went to our superiors and tried to find it and get it to them.”

One of his heartbreaking duties was to help some of the estimated 20-to- 50-thousand women who were sexually assaulted during hostilities. Major Ashford remembers one woman, in particular.

“She was not much older than a girl, a Muslim,” he says in a quiet voice. She impressed him with her steely courage and calm determination to rise above her brutal circumstances.

“I asked her what she was going to do. She told me, ’I’m going to live my life,’” the Major says with a look of admiration.

But the most taxing part of the job was the effort to get combatants to finally lay down their arms. It could be extremely dangerous, as the Major’s near-death experience in Pale, Bosnia showed. And it was not the only example.

Just days after that incident Major Ashford was assigned to accompany a translator to a village on the outskirts of Sarajevo. A Serbian general wanted to talk about arranging a meeting with senior officers to surrender.

When the trio—Major Ashford, a driver and the translator— pulled up to the bustling, heavily defended compound where the general was staying, pandemonium broke out.

“Soldiers ran up to the car, cursing us out, sticking guns in our faces,” he says. “We were surrounded by guys with AK-47s. They were three feet away. The translator was shouting, ’Don’t shoot. Don’t shoot.’ I told the translator and driver, ‘Don’t you blink. Don’t even think about it. Don’t you do nothing.

Don’t move.’”

He looked around. Armed soldiers ringed the perimeter. The driver had an M-16, the Major had a 9-millimeter. But it was no use. They put their hands on the dashboard where they could be seen, hoping no one would open fire, and stared at their captors, nervously wondering what was next.

“I’m going to die,” Major Ashford remembers thinking to himself. ”This is the second time since I got here. I am going to die.”

Someone finally yanked the translator from the Humvee and hustled him roughly into a building. Outside, the tense stand-off continued, everyone frozen, as if time had stopped.

“When the translator came out he was all white,” Major Ashford recalls. “He says ‘let’s back out very, very slowly and get out of here.’”

Major Ashford remained in the Reserves until his retirement in 2000. Then he worked for the U.S. Postal Service until his final retirement in 2017. His current interests are learning to speak Spanish and exercising to stay healthy.

Major Ashford’s wife and four children are proud of him. They’re thrilled that he’s been chosen for an Honor Flight. But the Major says he’s the one who is grateful.

“The Marine Corps and Army were the best things that ever happened to me,” he says. “I was a young, strong guy. But they gave me direction and pride. I learned to do my job, not for money or accolades, but because it’s how things are supposed to be done. Each place I went to I learned a little bit more. It was a great ride.”